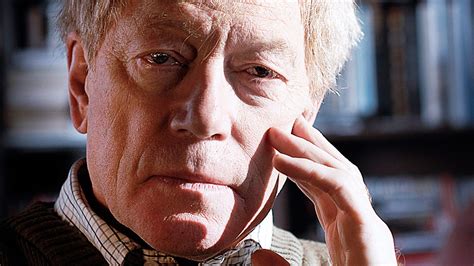

Roger Scruton (or now Sir Roger) has come a long way from the days when he was hounded from his professorship of philosophy at Birkbeck College in London for his conservative views.

The author of over forty books and numerous articles ranging from philosophy to hunting to wine to the church (namely, the Anglican Church); membership in the Royal Society of Literature; and, as indicated above, a knighthood—all of these things have established quite fully his reputation as one of the most serious and perhaps celebrated thinkers in the English-speaking world.

And, if you consider his time in Eastern Europe during the Cold War in service of the anti-communist underground, the argument might justly be made that his reputation extends farther than the Anglo-sphere. Both the Czech Republic (Medal for Merit, first class) and Poland (Lech Kaczynski Award) honored Scruton in 2015.

I have read a mere ten of Sir Roger’s books, which I have happily recommended to friends and family. But perhaps the easiest means of acquainting oneself with Scruton’s work is the recent Conversations With Roger Scruton, a book that is exactly what the title says. Scruton’s interlocutor is Mark Dooley, a philosopher himself, an Irishman, and a Roman Catholic.

These talks, conducted over a period of three days at Scruton’s Sunday Hill Farm (aka Scrutopia), cover topics as diverse as Scruton’s books: philosophy, politics, wine, hunting, architecture, sex, and farming. In almost all of these discussions a very rare and precious commodity, intelligent conversation, reigns.

But if there is one area in which I found myself somewhat mystified and, indeed, disappointed, it is the chapter on religion. Unlike some readers of this review, I have no problem in and of itself with Scruton’s Anglicanism, being within that community myself. But the Reformed Episcopal Church, of which I am a member, is certainly to the “right”—in more ways than one—of the worldwide Anglican community. And I knew very well that a “real” Anglican, British Church of England theology would likely prove, to say the least, somewhat more latitudinarian than what I am used to.

And so it is with Roger Scruton. His book Our Church: A Personal History of the Church of England had prepared me for this aspect of his faith, but nothing in my reading of it forewarned me of his eccentric or, to put it more strongly, heterodox opinion on the afterlife.

Few things are more fundamental to Christianity than the belief in eternal life that the crucifixion and resurrection make available to the believer. The gospel, the good news, amounts in a very large part to that fact: death has been conquered. In Conversations, the uneasiness about the doctrine is heralded by the sub-heading of chapter eleven “Rediscovering Religion.”

The sub-heading in question is a quotation from Scruton himself: “I think this life is probably enough.” What he means by that probably needs a little clarifying. John Adams in one of his last letters to Thomas Jefferson said in regard to living longer that he had had enough; William F. Buckley made a similar observation in an interview near the end of his life. But in neither case do I have any reason to suppose the opinion was meant to exclude the possibility of the afterlife. For Scruton, “enough” does.

In orthodoxy, as embraced by Rome, Constantinople, Geneva, and (at least doctrinally) Canterbury, the Incarnation is about a radical change in the state of man brought about when God the Son miraculously assumed the flesh to live a perfect life, die, rise from the dead, and then ascend in the flesh to the Father. It is part and parcel of the Christian faith that He—again, in the flesh—is the first fruits, the earnest, the down payment of the life we will one day have in Him everlastingly.

The odd reading of this doctrinal chain in Scruton’s faith results effectively in the expunging of the last two points of faith. To him, the Incarnation is a central mystery linked with the crucifixion. He writes: “I think one can do it [only live once] if one does recognize the absolute importance in our lives of moments of sacrifice, and the fact that we are seeking redemption and can only find it if God too is prepared as a sacrifice.” So far, so good, but he doesn’t stop there. “That is a mystical thing, wonderfully conveyed by Wagner in “Tristan and Isolde,” in which there is no suggestion of an afterlife, but only the great darkness in which you become what you truly are, which is nothing.”

In other words, in spite of the Church of the ages clearly stating that very God becomes very man as the only possible, perfect, and necessary sacrifice in God’s judicial system, Scruton’s theology posits that He becomes man and dies to reconcile us not to God but to death.

Mark Dooley, hardly an unsympathetic interviewer, nevertheless asks Scruton whether his view requires the same amount of faith as practiced by orthodox believers in their confidence in the afterlife. Of course, it does, Scruton responds, but he thinks his understanding, though not necessarily superior, still enables one “to feel the radiance of sympathy from” the perspective of, in Dooley’s words, “pure subjectivity unencumbered by place and time.”

By no means is it inconceivable that one might rejoice in reconciliation with God and, therefore, in the restoration of communion with Him, simply in order to die in peace.

I hope I do not do Roger Scruton an injustice by presenting that as his understanding. But just as certainly as the Richard Dawkinses of the world do not properly account for man’s belief in God as a plain fact of his history and existence, neither does Scruton offer an explanation for man’s hope in the afterlife, also a rather widely held belief. I firmly believe that there is one and only one faith that properly accounts for man’s lost state and the remedy necessary to redress it, but I also know that many religions describe a similar hope.

The transcendental, on which Scruton quite rightly places a great deal of emphasis, must have a relationship to all creation—allowing for the doctrine of a created universe. But what may be called a connection with the rest of creation becomes a bond between the transcendent Him and the part of creation that He made in His image.

It’s a bond that becomes undeniable—at least, sooner or later—in the fact of the Incarnate God who on the cross welcomes mankind back to Himself, even as The Book of Common Prayer (1928 version) states: “a full, perfect, and sufficient sacrifice, oblation, and satisfaction, for the sins of the whole world”—and for one reason, that we might enjoy eternal life in and with Him.

That’s a doctrine of our church in the broadest historical and revealed sense. I hope and pray Roger Scruton will live to embrace it. There can be little question that “pure subjectivity unencumbered by place and time” is best enjoyed in an eternal state.

Were there any more recent accounts if his having had a change of heart before his death?