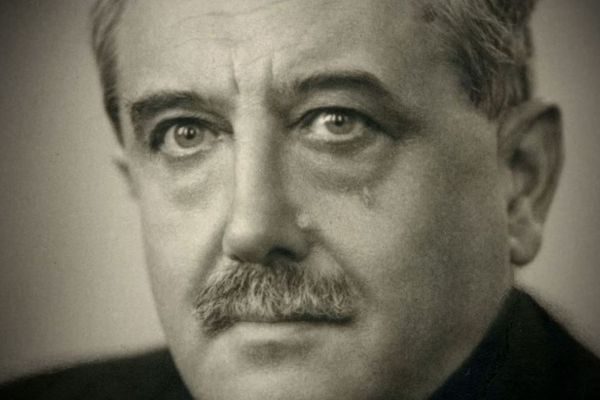

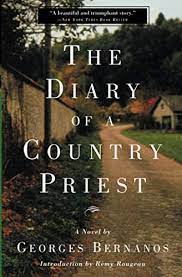

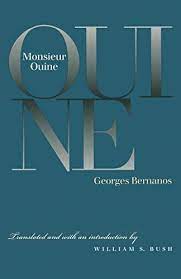

George Bernanos (1888-1948) was the most important novelist of the twentieth-century French Catholic Revival that included Léon Bloy, François Mauriac, and Julien Green, among others. Recognition of his importance is partially due to the wide popularity of his Diary of a Country Priest (1936) while his other six novels have been read in this country by a small few. Three of those six are every bit as good as the Dairy — Under the Sun of Satan (1926), Mouchette (1937), and Monsieur Ouine (1940).

These four major works, taken together with his apologetic and political works, as well as his play, The Dialogue of the Carmelites (published posthumously in 1949) create a written legacy that illumines like no other novelist the sufferings of sanctity in the midst of a world of trapped individuals isolated by their sin.

How many writers would have depicted the Devil as a character in a novel published in Paris during its Jazz Age when Josephine Baker danced and sang virtually nude at the Folies Bergère. His Under the Sun of Satan (1926) portrayed a priest who chooses the hard road to sanctity over Satanic temptation becoming a ‘reader of souls.’ It became a sensation in spite of the time and place of its publication.

Bernanos would never soften his depictions, in fact, with each major novel his embodiment of the struggle between good and evil, God and the Devil, would grow more profound and more shocking. His final novel, Monsieur Ouine (1940) became the key to understanding the life and work of the author.

Understanding the writer George Bernanos begins with three recognizing basic facts about his life.

First, He enjoyed an idyllic childhood in the village of Fressin in northwestern France in a region called Pas-de-Calais.

Second, he believed deeply in the Catholic faith in which he had been raised, reinforced by the piety and love of his beloved mother, Hermance, a direct descendant of St. Joan of Arc.

And thirdly, his attitude towards life, his Church, and his beloved home country of France were shattered by his experience in the trenches of the Somme and Verdun in World War I. In the December 1916 Battle of Verdun, the French suffered 377,231 casualties.

He witnessed day after day the unnecessary slaughter resulting from repeated ‘over the top’ orders, meaning out of the trenches, were given by an officer corps which thought more about the pride and honor of France than the lives of young men. Many of them hoped to avenge the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 and the humiliating occupation of Paris by the Hun.

In the ‘No-man’s land’ between French and German trenches, Bernanos saw innocence destroyed on a daily basis by what he called ‘The Old Men’ who had no regard for the lives and futures of France’s young men. The Old Men included not only the politicians and military men, but also the Church leadership who supported their fellow Old Men in the name of ‘Catholic France.’

The war changed Bernanos forever. After struggling with post-war despair, his experience made him an even more committed Catholic, but one willing and able to call out his Mother Church for its false allegiances and its compromises with the petty bourgeoisie. So willing was he to denounce his own country, Bernanos moved with his family out of France to Spain and eventually to a Brazilian jungle where he lived for seven years. From there he shot out missive after missive, broadcast after broadcast to a nation that did not listen.

Bernanos became a prophet. His message was simple at the surface — France must embrace its lost monarchy and in doing so reconfirm its Catholic past and identity. France, in other words, must be reborn under the flag of its saint, Joan of Arc.

His reputation had been built on the success of two novels, Under the Sun of Satan (1926) and The Diary of a Country Priest (1936).

Bernanos had been hailed the equal of Dostoevsky by no less than the great French writer and diplomat, Paul Claudel. Like the author of The Brothers Karamazov, his subject was good and evil, God and the Devil.

Out of the slaughter of the innocent he witnessed in the War, childhood innocence itself became his symbol of spiritual recovery, the door to redemption, the recovery of the purity we all desire. This is why the Curé in Monsieur Ouine says to village doctor, Dr. Malepine,

“Rather than the obsession with impurity, you’d do better to fear the nostalgia for purity” (213).*

Why? It would obliterate the doctor’s scientific and deterministic worldview.

But after any easy generalizations, the complexity of Bernanos’s message is encountered by the readers in his depiction of post-war France, where different kinds of trenches have been dug, trenches of isolation. What he sees is a France, along with all human existence for that matter, itself lost in a mire, literally, a concoction of self-interest, status-seeking, pleasure-seeking, materialistic greed, and boredom.

If the prophet is a novelist, he must employ indirection. He cannot preach, or, at least, he must let any preaching come from the mouths of his characters. Monsieur Ouine acts the role of a secular priest preaching his crafty cynicism, while the Doctor and Mayor opine publicly on what makes the world tick.

But even among the competing voices, his form of his fiction, especially, Monsieur Ouine, follows few straight lines. His attempt at writing in straight lines, becoming more accessible, in The Crime (1935) was a failure. His voice was tuned to the fallen actuality of existence and couldn’t conform to the template of a detective novel.

Readers of Bernanos must come to appreciate that the form of his fiction corresponds to the world he depicts, a chaos of atomistic individuals seeking their own self-interest, ignoring the well-being of others and their community. Bernanos despised ‘facilite’ or ‘ease’ in fiction; he viewed his novels as a kind of spiritual exercise for the reader, just as it had been for the writer.

How can a writer attempting to reveal the pervasiveness of evil and sloth accomplish that didactically, abstractly, in such a way that can be read once and forgotten like the morning’s news headlines? Form helps to convey meaning, not necessarily to make it clearer but to put form and content in alignment.

Let’s recall here that Bernanos was never a Manichaean, viewing the world as a struggle between the powers of light and dark, good and evil. He viewed evil as nothingness, presaged by the experience of nihilism and despair.

The Devil who shows up in Under the Sun of Satan represents no higher power. His wily and gratuitous deceptions prick the earnest conscience of Abbé Donaissan, and he turns his back on the pesky horse trader.

We never see the direct connection, the cause and effect, between Ouine and the village whose pervasive ennui has erupted into madness after finding the dead young boy in a muddy stream. Madam Marchal, however, tells Steeny, “You’d think this whole miserable village had been put under a spell. Since the murder of the little cowherd it’s not recognizable anymore, I swear!” (226).

Ouine’s connection to the town is seen manifestations of condemnation, fury, and insanity issuing forth in acts of cruelty, murder, and suicide. This is a connection he does not deny; in fact, he brags about it, “I was hungry only for souls” (251). The spiritual emptiness of the village is further exemplified by the constant encroachment of water which becomes deeper and muddier until a “black ooze” covers the floors of the chateau where Ouine lives. The young cowherd, attempting to deliver a message from Ouine, gets lost in “torrents of water.” Think of the two Mouchettes in his earlier novels who took their lives in water.

Ouine himself is described like a fish in a muddy pond, a “jelly-fish at the bottom of the sea.” He has a massive body of pure fat, with no muscle tone, like the body of an aged woman. His hands feel “slippery” to Steeny.

When Ouine tells Steeny in one of the opening scenes, “I will teach you to love death” (21), this is a pedagogy of boredom and eventual nothingness. “The world has no end,” (28) he tells Steeny, meaning there is nothing greater than oneself to seek, no standard to be measured by, nothing that deserves our commitment, and certainly no heaven.

Thankfully, Steeny will resist and break free from the “master.” Indeed, for all its bleakness, Monsieur Ouine ends on what might be called a happy note. We should remember the innocent goodness of Steeny’s friend Guillaume, a cripple and the grandson of de Vandomme, who plants a seed when he tries to warn him to stay away from the former professor. Only later do we learn that Ouine, as a fatherless schoolboy, was molested by his teacher. And we are reminded that Ouine was once an innocent child who now seeks to replicate the violence he once suffered.

Yes, in Monsieur Ouine, the patient reader has to suffer too, along with the narrator, the characters, and the community he describes.

In this, Bernanos stands in good company — Dostoevsky comes first to mind. But also Melville, Faulkner, Cervantes, Mann, Proust, Joyce, O’Connor, Kafka, and Cormac McCarthy.

The novel Monsieur Ouine jumps from one scene to another with few transitions with little contiguity. he destroys what he appears to affirm, recall his long talk with the Curé: his seemingly kind words are actually an attempt to empty him of spiritual commitment. Madam Marchal, the midwife, has Ouine’s number:

“…the simplest thing in his mother, becomes unrecognizable. Thus for example, he never speaks ill of anyone, and he is very good and very indulgent. Yet in the depths of his eyes you still see something making you understand how ridiculous people are. And if you take away that ridiculousness, you lose interest in them, they seem empty, and life itself seems empty; it’s a great empty house where everyone enters , one after another. . . But they never meet” (222).

In the novel, characters begin speaking who are not identified until pages later. Scenes are often nightmarish and sketchy such as the attempt of Jambe-de-Laine (Wooly Legs), to kill Steeny with her horse and carriage and the sudden emergence from the woods of an injured woodcutter from Alsace. The suicide scene of the young married couple, Eugene and Helen, feels perfunctory, particularly because Eugene is one of the two innocents, along with Guillaume, in the novel.

The visit the night before of Old Man de Vendomme Eugene was also minimalistic. We are not made aware whether or not Vendomme has considered his daughter’s fate if her husband kills himself. His only thought is for protecting an imagined nobility in the eyes of others, who never cared in the first place.

We see that no one, except Steeny, cares about finding out who actually killed the young boy. At the funeral, only the priest and Jamb-de-Laine appear to care about the child’s death. The mayor, Arsène, sees it as a threat to his personal status while a gendarme starts snoring while sitting next to the displayed corpse. The doctor views the boy without compassion, only as a specimen to be examined. The villagers are so anxious to put the boy’s death behind they rush to judgment of an innocent man. Ouine doesn’t care, and he knew “the little hired boy from Malicornes” who brought the milk each evening (28). And he’s the one who sent him out into the night on an errand to Steeny’s house.

Steeny, too, is a child in potential danger when Ouine turns his arresting gaze on him. As one Bernanos critic puts it:

“The fate of the children in the novel’s ‘world of old men’ is the most haunting theme of Monsieur Ouine, but that is at least in part because it is related so closely to the inevitable decay of a world that does not treasure and protect its children” (Gerda Blumenthal, The Poetic Imagination of George Bernanos: An Essay in Interpretation, The Johns Hopkins University Press (1965) p. 27.

Readers will recall that Steeny grew up in a lesbian household with his mother and his English governess who formed a tighter bond between themselves than the mother has to her son. When he rides away in the carriage with Jamb-de-Laine it is because he wants to escape from, to anticipate the Curé’s funeral sermon, a dead home. But he faces the danger of a corrupted and cold-hearted village, “the thin blonde road, twining around itself like a viper going nowhere.” (9) Both Mouchettes from his two previous Bernanos novels came from similarly dead homes.

The main character himself is a master of deception, so much so, that readers themselves have to distinguish between his lies and his unexpected moments of honesty. The most surprising moment of all comes on his death bed, “I can now see to the bottom of my own depths, there is nothing stopping my gaze, no obstacle is in the way. And there is nothing there” (243). The dying Monsieur Ouine when, forced to look at himself for the first time, he concludes, “It is I who am nothing” (251).

The Curé’s sermon in Chapter Thirteen at the funeral of the murdered child is, for me, the apex of the novel. When the Curé of Fenouille announces, ‘This parish is dead,’ the reader is surprised. Why? Curé has already been shown to be weak when he hands over private letters to Ouine. Here the Curé speaks in a voice where nothing is held back, nothing is moderate, mannerly, or appropriate. Bernanos is speaking prophetically to the entire Church and all its parishes. His message, sadly, remains relevant. More about that, later.

He began Monsieur Quine in 1931 but left it unfinished to write The Crime published in 1935 and The Diary of the Country Priest published in 1936. Thus, the priest’s sermon had already been written before Bernanos saw the Church sell its soul once again. The Vatican applauded the 1935 invasion of Ethiopia by Mussolini’s fascists and the rise to power in Spain of Franco’s Falange Party (1936) — both dictators using the name of Christ to justify the imposition of their power. Bernanos observed the growing genocidal violence of the Falange from nearby Majorca which must have reawakened his gruesome memories of the WWI trenches, remarking, “The Spanish experience is probably the principle event of my life.”

Given what I have previously said about the impact of WWI on Bernanos, I think this comment refers to how the Spanish Civil War completely severed his relationship with the right-wing Action Francaise which supported Franco, but more importantly, destroyed his belief in any kind of political solution, especially from the Right, to his country’s moral and spiritual decay.

The subsequent decline of France’s Catholicism, forecast by Bernanos among others, has been well-chronicled and was then punctuated by the philosophies of deconstruction and postmodernism, both French-born, that emerged from the slime in the late 1960s. Ouine’s view that there “the world has no end” (28) was made into a philosophy and exported to the United States where it has been embraced fully by secular academics in search of a cause.

The narrator of Monsieur Ouine describes the words of the Curé emerging “like a sword from its sheath” (164). This is the same Curé who had already flunked a test of his character during his long conversation in a previous chapter with Ouine.

However, like Steeny whose seduction by Ouine begins the novel, the Curé recovers himself. He turns his back when Ouine urges him to moderate his remarks at the graveside. Overcoming Ouine’s deceiving pleas for moderation and his attempt to drive him to despair, the Curé delivers what must be one of the most powerful messages in Bernanos’s oeuvre. He approached the coffin of the raped and murdered boy through the muddy ground.

“What …,” said the poor man with his sad voice, “what have you come looking for this morning? What are you asking your priest to do? Prayers for this dead child? But I am helpless without you. I’m helpless without my parish, and I haven’t got a parish. There’s no more parish here, my brothers . . . just a commune and a priest, and that’s not a parish” (165).

(We can understand here why Hans Urs von Balthasar entitled his book, Bernanos: An Ecclesial Existence. Bernanos does not conceive of the Christian life or sanctity itself in isolation from the community of believers.)

As Bernanos sees it, the priest’s description of his village extends to the whole of Europe in the wake of the First World War. This is a judgment that will be confirmed by France’s pathetic attempt to appease Hitler in 1939 and its even more pathetic attempt to counter the Blitzkrieg of Hitler’s armies in the Second World War.

At the grave of the young boy, his boots covered with mud, the Curé connects his village to all of humanity:

“They are always talking about the fire of hell, but no one has ever seen it, my friends. For hell is cold. It used to be that the nights weren’t long enough to wear out your malice, and you got up each morning with your breasts still full of poison. But now the devil himself has withdrawn from you. Ah, how alone we are in evil, my brothers! The poor human race dreams from century to century of breaking that solitude — but it’s no use! The devil, who can do so many things, will never succeed in founding a Church, a Church that will put in common both the merits of hell and the sin of all. From now until the end of the world, the sinner will have to sin alone, always alone — for just as we die alone, so also do we sin alone. The devil, you see, is the friend who never stays with us to the end” (my italics, 171).

Yet, in the novel there are those, other than Ouine, who celebrate the decomposition of Christianity. Here the scientist, Doctor Malipine, shares his ‘enlightened’ view of life with the mayor:

“The hour is coming when, on the ruins of the old Christian order, a new order will be born that will indeed be an order of the world, the order of the Prince of this World, of that prince whose kingdom is of this world. And the hard law of necessity, stronger than any illusions, will then remove the very object for clerical pride so long maintained simply by conventions outlasting any belief. And the footsteps of beggars shall cause the earth to tremble once again” (177).

Therefore, Monsieur Ouine should not be read as primarily the drama of Steeny’s struggle his master Ouine, or the detective drama of who killed the young cowherd, or the struggle of Jamb-de-Laine to free herself from servitude to Ouine, it is a novel about the entire village of Fenoiulle, a community whose lack of Faith is embodied by the mud, water, and filth that engulfs the town. And the village itself represents the whole of human society. Bernanos once referred to his novel as “Job’s dungheap.”

His nothingness, we are shown, is not absolute; it cannot endure because nature, represented by the morning sun Ouine detests, abhors a vacuum. That sun has its analog in the thirst for purity that inhabits the hearts of every man and woman regardless of their moral and spiritual status. This thirst, which could be called the natural love the human creature has for his Creator, is the ground of any future redemption, any transformation of a village into a true parish. This thirst is the ground of hope, the hope for salvation.

The much-admired French Catholic writer, Rene Giraud commented:

“Bernanos’ apocalyptic vision was not pessimistic since it gave a meaning to evil.”

Knowing its meaning, we are then equipped to fight it. We fight every impulse to conform to the world, its expectations, its standards of success in life. We fight the isolation of modern life, its loneliness, hearing cries of desperation and responding.

Bernanos would have us put our hope in the creation of true parish-centered or church-centered communities where despair and cynicism, the will to self-destruction, can be met with the embrace not only of acceptance but also a shared aspiration towards life’s true end, sanctity and Eternal happiness with God.

But the fight cannot even begin if we do not recognize the depths to which we have fallen, how much our institutions have become the enemy, the purveyors of nothing. This is one of the central achievements of George Bernanos: he does not let us look away from our age of long spiritual decline.

Bernanos would have us be uncompromising, unwilling to settle for half-measures or outright dismissals. The battle is beginning to rage, one that I think Bernanos would applaud, and each of us must be part of it.

*Page numbers are from the translation by William S. Bush, Bison Books, 2000. Prof. Bush was dear friend of mine who died far too young.