Catholics of my generation probably only dimly remember, if at all, the furor provoked among Catholics by films in the 1950s directed by Luis Buñuel, Los Olivados (1950); Roberto Rossellini, The Miracle (1951); Otto Preminger, The Moon is Blue (1953); Elia Kazan, Baby Doll (1956); Roger Vadim, And God Created Woman (1956); and Billy Wilder, Some Like It Hot (1959).

Most people to think of today’s “culture wars” began in the 60s — Vietnam War protests, Hippies, and Nixon’s Watergate — but the tremors of that struggle can be traced back to the postwar period when major filmmakers decided to free themselves from the bonds of the Catholic-inspired Motion Picture Production Code that had governed Hollywood productions since 1930.

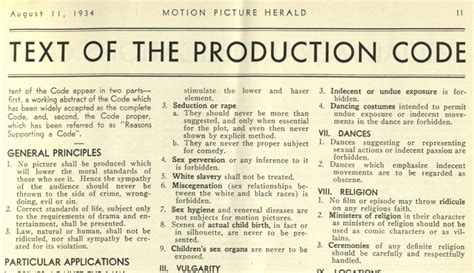

It was Hollywood’s fear of Catholic opinion that led to the creation of the Code in the first place. Martin Quigley, a Catholic layman and film writer, had been pushing for such a code since the early 20s. He asked Rev. Daniel Lord, S.J, of St. Louis University to draft something for moguls at Warner Brothers, MGM, 20th Century Fox, Paramount, and RKO. Father Lord had already been a technical advisor to Cecil B. DeMille for his silent film version of King of Kings (1927). What Father Lord drafted is far from a puritanical screed. Though it does set definite limits on what films can show on the screen, especially about sex, the MPPC is highly sophisticated in a way that reflected the work of a deeply educated and aesthetically sensitive Jesuit.

The major studios, however, assumed they could play fast and loose with the Code’s requirements, but Catholics, in particular, did not let them get it away with ignoring it. The National Legion of Decency was founded by Catholics in 1933 to fight against the immoral influence of Hollywood films, which, it must be said, were challenging the moral boundaries of mainstream America. That led to the hiring in 1934 of another Catholic layman, Joseph Breen, to head of a new Production Code Office. (The films between 1930 to 1933 are now called the “Pre-Code” era mainly due to the sex, homosexuality, lesbianism, and unredeemed violence that they portrayed.)

Breen had to approve every script before it went into production which gave him considerable power. Breen himself was neither a prude nor an unreasonable man, but producers, directors, screenwriters, and actors naturally grew weary of his ‘censorship.’ One magazine wrote in 1936 that Breen had “more influence in standardizing world thinking than Mussolini, Hitler, or Stalin.”

The power of the Production Code Office held sway through the end of WWII. As the “Mad Men” decade of the 50s began, filmmakers began to challenge Breen, the Code, the power of the National Legion of Decency. The first direct challenge came from the Italian director, Roberto Rossellini and the U.S. film distribution company that brought to film to be screened in New York City.

It was 1950, Rossellini’s film, The Miracle (Il Miracolo) opened at the Paris Theater, on 58th just west of 5th Avenue, one of the oldest ‘art houses’ in the United States. The National Legion of Decency denounced the film as “anti-Catholic” and a “blasphemous mockery of Christian-religious truth,” giving it the C rating — signifying “condemned” — a judgment that was previously feared by Hollywood studios. The Legion’s rating led the New York State Board of Regents, in charge of film censorship, to revoke its license to be shown in movie theaters.

Francis Cardinal Spellman of New York never saw the film but issued a statement to be read at every Mass in every parish of the New York Archdiocese. He condemned it as “a despicable affront to every Christian” and “a vicious insult to Italian womanhood,” eliciting demonstrations in front of the theater where it was being shown. The protesters carried signs which read, “This Picture Is an Insult to Every Decent Woman and Her Mother,” “Don’t Be a Communist,” and “Don’t Enter the Cesspool.” Nine years earlier, Cardinal Spellman’s public condemnation of Greta Garbo’s Two-Faced Woman (1941) had caused MGM to withdraw and re-release an edited version.

But a sea-change had occurred in American culture following World War II, and the movie’s distributor Joseph Burstyn, sensing this, initiated a lawsuit that made its way to the U.S. Supreme Court. In Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson, the Court ruled the film’s artistic expression was guaranteed by the First Amendment — freedom of speech. At the same time, the Court’s decision overthrew legal precedents going back to 1915 that allowed the public censorship of films.

The Supreme Court decision marked not only an end to the power of the Code but was also a sign that the cultural clout of Catholics was coming to an end. However, by putting it so bluntly, I don’t want to be misleading. It was a certain kind of clout, a form of Catholic Puritanism, that was defeated.

The sophistication seen in the original Code written by Rev. Daniel Lord, S.J., had been turned into a fear-driven attempt of the Legion to act as parents looking out for a nation of impressionable children. In doing so, the Legion’s condemnations showed no appreciation of, or respect for, film as an art form, in the manner contained in Rev. Lord’s original Code.

It was by “crying wolf” too often about artistically important, well-made films, the Legion and its supporters became irrelevant. These denunciations were based not on seeing the actual films but what was read about them. Thus, a simple, one-sentence summary of The Miracle, certainly makes the condemnation sound plausible: “A poor shepherdess named Nanni who believes herself to be the Virgin Mary is seduced with liquor drink by a wanderer whom she thinks is St. Joseph.”

Yet, after viewing the film itself, one Catholic critic called The Miracle a story of “unregenerating suffering.” What is still considered a consummate performance by Anna Magnani, as a “holy fool,” demonstrates how easy it is to caricature in verbal terms what is far more complex when seen on the screen. As was mentioned, Cardinal Spellman never saw the film about which he required all his priests to read a statement from their pulpits.

It should be added that the same year, 1950, Roberto Rossellini made what is arguably the best film ever made about the life of St. Francis, The Flowers of St. Francis (Francesco, giullare di Dio). Also co-written with Fellini, the film about St. Francis was called, in l995 by the Vatican, one of the 45 greatest films ever made.

The moral of the story? Catholics lose cultural influence when they act like parental arbiters of public taste, especially when they refuse to acknowledge excellence in works of art they find somehow objectionable or dangerous.

Less than a decade after the furor over Rossellini’s film, the United States would elect its first Catholic president, and during the same period a number of Catholic writers would become celebrated among the elites of the literati, including Flannery O’Connor, J. F. Powers, Graham Green, Muriel Spark, Thomas Merton, Walker Percy, and Paul Horgan. All of these writers would not have passed the scrutiny of those at the National Legion of Decency.

Merely contrasting the work of these celebrated Catholic writers with the narrow Catholic mentality behind the condemnation of films by Buñuel, Rossellini, Preminger, Vadim, Kazan, and Wilder provides a lesson that many Catholics, 67 years later, have still not yet learned.

Further reading:

William Bruce Johnson, Miracles and Sacrilege: Roberto Rossellini, the Church and Film Censorship in Hollywood, University of Toronto Press, 2008.

Laura Wittern-Keller, Raymond J. Haberski, The Miracle Case: Film Censorship and the Supreme Court, University Press of Kansas, 2008