During the years television programming fully hit its stride, my mother could safely park my sister and me in front of the TV in the assurance that we would watch happily and leave her to other things. It’s an old story: the tube was a convenient babysitter and, once the installments were paid up, a pretty economical one at that.

All that TV watching left me with permanent memories or, if you prefer, mental scars that will never completely heal. I recall quite a few shows, many of them sitcoms, such as “My Little Margie,” just to pick an example. It starred Gail Storm and Charles Farrell, the latter who made his name with Janet Gaynor in a baker’s dozen of early thirties musicals and some silent gems. Memory tells me “My Little Margie” was funny. But maturity, a thing people once took more or less for granted, ran its predictable course, and the series seen now is not only not very funny but often contrived. If I had the time to watch it, I wouldn’t.

Many things in life follow the same pattern. What we thought peerless in the hazy days of childhood or, worse, adolescence proves mediocre or poor as the years advance. Oh, if only the same progress could be plotted in the life of the American college campus. But no. Across America, something very like an old fifties sitcom is being re-run. Some of us may say we’ve seen it before and it’s not as entertaining as it was the first go-round, but for the players and especially the scriptwriters the “show” is as exciting as it was when it first appeared.

What I’m referring to is campus radicalism, which, never content to express itself in the forum of civil debate, must light up the Molotov cocktails and party. The lead actors are difficult to list or, for the rare university president with the backbone, expel because they’re so often faceless, intentionally hiding behind masks and disappearing into mobs of like- or lack-minded comrades.

Their targets are well known by now: Charles Murray, Heather Mac Donald, Betsy DeVos—intellectually gifted, often academically credentialed, published, and philanthropic men and women who have the misfortune to be associated with the intellectual Right. Indeed, because the radical Left has no time to hear them out, one may safely argue that being conservative and showing up at any school to speak is all it takes for a mob to gather and begin heckling—and that’s when they’re on their best behavior.

Surely, this was not always so. Universities in the thirties could not have been entirely immune to controversy, but, allowing that, Columbia and Berkeley did not burn, and speakers of the “wrong” stripe were not manhandled by gaggles of masked thugs. So where did it all begin?

Assuredly, many deserve their fair share of blame for the demise of civil discourse on campus, but to the degree that this lamentable state of affairs may be traced to the radical sixties, Professor Herbert Marcuse, if he were still with us, would have a lot of explaining to do.

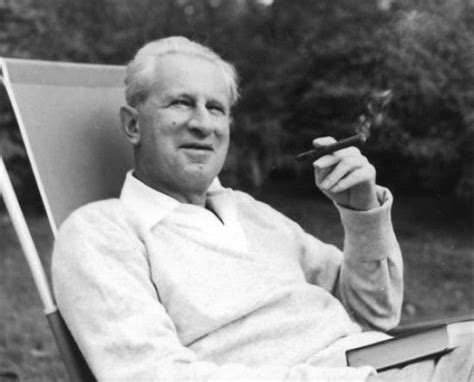

A member of the leftist Frankfurt School, Marcuse (1898-1979) fled the Nazis in the 1930s and landed, after a brief stint in Paris, in New York at Columbia. From there he would move to Brandeis and finally to the University of California at San Diego to bask in the sun and the limelight. He took American citizenship in 1940 but somehow never fully imbibed the Jeffersonian spirit of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness for all. That’s another way of saying he was on arrival and remained to his death a Marxist, a dialectical materialist to the core.

From his secure academic chair, Marcuse proclaimed something he called of “Repressive Tolerance” in an essay with that very title from 1969. Such a doctrine may seem a contradiction in terms but only if one defines tolerance according to old-fashioned logic and experience as a public virtue people in largely pluralistic societies exercise in recognition of the fact that no one holds a monopoly on the truth.

Not to Marcuse. Pour a bag of Marxist flour (or quick-dry cement) into the cake mix, and you get an entirely new definition:

“Liberating tolerance, then, would mean intolerance against movements from the Right, and toleration of movements from the Left. As to the scope of this tolerance and intolerance: . . . it would extend to the stage of action as well as of discussion and propaganda, of deed as well as of word” (Critique of Pure Tolerance, p. 109, quoted in Eliseo Vivas, Contra Marcuse, p. 175).

That’s quite a definition, maybe even an original one if we ignore writers like George Orwell.

The ABCs of politics ought to teach us that toleration doesn’t mean much when it is applied to people who agree, who march in lockstep . . . together . . . as one. Tolerance is, in the strictest and most obvious sense, irrelevant within the party. It’s those other people, the ones with whom you disagree, that you must tolerate.

Hence, within a state of mutual sufferance, people hope they will, through trial and error, arrive at a consensus or a place where they might at least respect one another’s rights. I may think my neighbor is a fool to watch TV eighteen hours a day when he might be enjoying Dostoevsky, but apart from persuading him to cut the cord, I must learn to accept his preference, however Philistine it appears to me, and let him live in peace.

That’s perhaps a very small instance of tolerance in a free society, but the principle is clear.

For Marcuse, who as a famous photo testifies, loved his cigar and easy chair, the stench of the affluent West was, in a word, intolerable. Any group who tried to defend free institutions and free enterprise deserved nothing less than the iron fist of repressive tolerance. What that might mean politically was something about which Marcuse, always vague on the details, never fully elaborated. But students in the sixties, eventually the tenured Ph.Ds. of today, latched onto his ideas, and American university life was changed forever.

Marcuse’s thought suffered something of an “eclipse” after his death, as The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy declares, but recently “there has been a new surge of interest in Marcuse.” Surge indeed. Like a tidal wave. Or an old sit-com: “My Little Marcuse.” Alas, a little goes a long, long way. Ask Charles Murray or Heather Mac Donald.