Are you a citizen? The question may sound strange, and, surely, for the last 140 years of our country’s history, nearly everyone could have answered in the affirmative. Yet today millions of people inside the borders of the United States are not citizens and likely don’t even think of themselves as such.

Another group—smaller, privileged, and technically citizens—views itself as an elite, a modern-day aristocracy, which alone can develop policies to guide the country in a direction befitting a twenty-first-century state.

In between these two groups is the middle class: hardworking, law-abiding citizens who define themselves on their loyalty to what amounts to the American creed as stated in the Declaration and Constitution. Though not on the verge of extinction, they are seeing their class shrink at a steady pace due to loss of voice and income. The next step for them follows the path down to the status of subject or peasant.

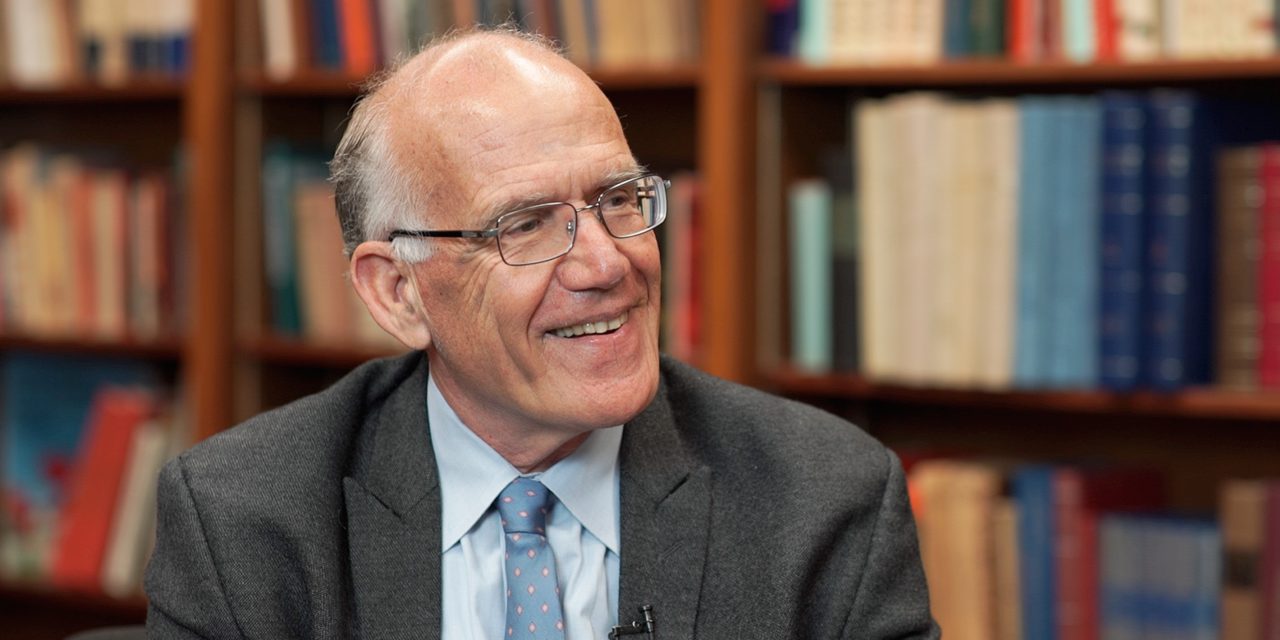

In his book The Dying Citizen (Basic Books), Victor Davis Hanson follows the course of this alarming decline of citizenry through a carefully reasoned and historically plotted argument. His first task lies in definition of various members of society through the ages, the peasant, the tribesman, the resident: categories of people Hanson identifies as “pre-citizens.” One can hardly gainsay his assertion that these types have comprised a large majority of people throughout history.

The peasant, frequently landless and dirt poor, lives and survives to produce crops or goods that he cannot claim as his own, living in hope that his lord will grant him something above subsistence. The tribesman may have a more-or-less defined territory that he calls his own, which surely puts him a step above the peasant; nevertheless, he regards his existence according to blood. Are you a fellow Sioux, Watutsi, or Malay? Your humanity and possibly your survival may depend on how you answer that question.

As for the resident, he may very well define himself according to his country of origin—as Canadian, Mexican, or Chinese—as well as by its customs, but he resides somewhere else. That “somewhere else” may have its bonuses in social services and opportunities for work, but the resident remains in his heart of hearts and frequently as a matter of plain fact a peasant, subject, or citizen of his original land. There is no new home.

The challenges the new influx of “pre-citizens” pose for the citizens of the United States are easy enough to pinpoint: higher taxes, higher crime, and, where laws are loosely enforced, broadly interpreted, or overtured, skewed elections. Visible and equally important are the cultural changes wrought by the new residents, most notably Hispanics, in their successful demands for dual-language signs and forms, their publicized crimes, and their occasional exhibition of antipathy to the host country. As to the latter development, Hanson recalls the 1996 United States-versus-Mexico soccer contest at the L.A. Coliseum, in which the overflow crowd booed the host team when it took the field, with some spectators throwing cups of urine on the U.S. players. That may be called many things, but assimilation isn’t one of them.

The crisis of virtually unchecked immigration, primarily on our southern border, is not without remedy. Intelligent policy, a clear sense of the law and the necessity of enforcing it, and the courage to ignore both a hostile press and political pressure—all the stuff of statesmanship—are possible but increasing difficult. Over the years, Democratic Party leaders and their allies in the media have been brazen in their insistence that millions of immigrants legal and, increasingly, illegal will build a permanently reliable voting bloc.

Anyone who tries to foil the gambit may find himself publicly excoriated and shamed into silence.

Due to the way Washington politics have evolved, when an administration attempts to limit immigration and apply statutes for the deportation of lawbreakers, left-leaning judges and functionaries of the administrative state (the “unelected,” as Hanson describes them) block the law at every turn. Whatever one may think of former President Trump’s fulfillment of his promises about the border wall and Mexico’s paying for it, traditional and legal immigration enforcement were, despite some successes, severely hampered by the courts and recalcitrant bureaucrats during his tenure. And the lack of accountability of these obstructionist officials makes it all the more difficult to achieve effective policy.

On another front, the rise of an equally unelected global elite has made a borderless world, where financiers and investors are kings, the foundation of a grand strategy. As Hanson says, this goal accounts for “their contempt for supposedly ossified nationalism and local government.” Style them as you will—Davosi, NGOs, Great Resetters, or, as Hanson prefers, Globalists—they see themselves as a new aristocracy, a tribe of the ultra-rich, who alone can lead the unwashed (“deplorables,” as Hillary called them) into the sunlit, stratified society of the future. It’s little wonder that some of them see China as their model.

Is the triumph of these powerful forces of a new order, so different from one another but all threatening, guaranteed? Their wealth, numbers, and ability to silence opposition seem to say so. Hanson is no Pollyanna where the future is concerned; all he can offer is the hope that the citizens, even as their numbers decline, will keep on trying. Not a very hopeful outlook.

But in the aftermath of The Dying Citizen’s publication, a gubernatorial election in Virginia and recalls of leftist schoolboard members across the country showed citizens cannot only try but succeed in reclaiming the privileges and liberties that the constitution was ratified to protect. It may well be that the “citizen” of Hanson’s title was not really dying at all; he was just sleeping.