It hasn’t been so very long ago that my wife and I were at a church social, sitting at a table with a very literate teacher at a fine classical Christian school. When I mentioned that I’d been reading about Samuel Johnson, she immediately laughed. “Oh,” she said, “the man who wrote the dictionary with all of those outlandish definitions.”

That reaction—certainly in Great Britain and, to a large extent, in America—would have once been unthinkable. All schoolboys and, as education became more and more coeducational, schoolgirls knew their Johnson, likely through the various essays from the Rambler and via James Boswell’s inimitable biography. But nowadays even a well-read teacher of mathematics who knows her Dante better than most and has directed many of the school’s annual plays (Shakespeare, Molière, Rostand, among others) may know next-to-nothing about the second most quoted figure in British literature.

Who was Johnson? Thanks to James Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson, a great deal. He was born in 1709 in Lichfield, Staffordshire, a cathedral town, to Michael Johnson, a bookseller, and his wife Sarah. As a child, he contracted scrofula, a lymphatic disease, from the infected milk of a wetnurse, leaving him blind in one eye, half-blind in the other, and deaf in one ear. Yet he had, at least from the age of three, a prodigious memory. Boswell recounts that when Johnson was still very young, his mother set him the task of memorizing the collect for the day from The Book of Common Prayer. Immediately, she headed upstairs, but before she reached the top, he called out that he had already memorized it. And, indeed, he had.

During his school years, his handicaps were troublesome, but he learned to box and swim, both of which he did well. He was congenitally averse to the pitying attempts of others to help him. Once when he was groping his way home, a teacher tried to turn him in the right direction, but he slapped the helping hand away. Later at Oxford, where he had enough funds for one year, he angrily threw into the quad a pair of shoes someone had left at the door.

Johnson never did earn the degree he coveted (except for the M.A. he received later for the dictionary), yet he recognized years after that the failure of funds had probably saved him from an undistinguished, narrow life as an obscure don. But fame was years into the future. Before that came, he was doomed to a life of hardship.

Marriage to Elizabeth “Tetty” Porter, a widow twenty years his senior, led to an attempt at founding a boys’ school. It attracted two pupils, one of whom was David Garrick, later the most celebrated actor of the age. When the school foundered, Johnson and Garrick headed for London to make their fortunes. In time, Garrick succeeded, while Johnson worked for years as a Grub Street journalist, turning out copy on demand for Edward Cave’s Gentleman’s Magazine, sending enough money to house Tetty in the more salubrious suburbs. Johnson was later known to say, “He who is tired of London is tired of life,” but life there was hard. To remain near Cave’s offices, he stayed in the city, renting a small garret or, often as not, sleeping in the doorways of old houses after wandering the streets.

Some successes kept Johnson going. His poem “London,” published, as all his early writings were, anonymously, was a great success, and his “reports” of parliamentary debates for Cave had a wide audience. Prohibited by law from attending the sessions, Johnson simply made up MP’s speeches and exchanges and mimicked their styles so faithfully that for years collections of their oratory included, unknown to the editors, speeches that were actually Johnson’s.

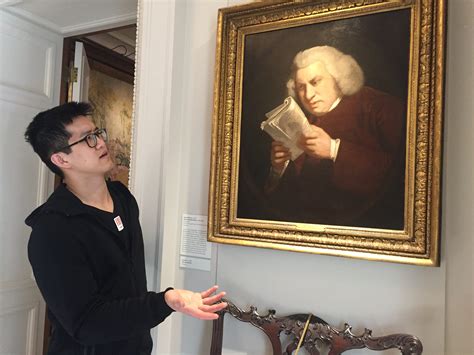

Johnson may have gained a small amount of satisfaction from these successes, but fame eluded him. His only play, “Irene,” was not staged until years later and all attempts at patronage, notably from Lord Chesterfield, got him nowhere. Then everything changed. His offer to a publishing group for a dictionary of the English language was accepted. With the help of six copyists, he completed the task in nine years, compiling a work of over 40,000 words, illustrated with 114,000 quotations (the first dictionary to do this). To keep things in perspective, it took a French committee nearly seventy years to produce their dictionary.

As for the eccentric definitions, they are unjustly famous, overshadowing most of the words that Johnson defined in a manner biographer John Wain called “masterly.” Entries, such as, “Oats: a grain, which in England is generally given to horses, but in Scotland appears to support the people,” were intentional jokes. (Johnson had at least one Scottish amanuensis for the project.) But the greatest testimony to the value of the dictionary is that it remained standard in Britain until the completion of the Oxford English Dictionary over 150 years later.

Johnson’s wife never saw her husband’s fame for the great undertaking; Tetty had slipped steadily into alcoholism and died in 1752, three years before the dictionary’s completion. The marriage was far from happy, but Johnson’s grief was real, and his written prayer—a model of humility and piety—testifies to the depth of his sorrow. However, she did see the publication of his magnificent satire “The Vanity of Human Wishes” and the series of essays The Rambler, models of their art.

King George III, determined, as Wain points out, to reward men of genius in his kingdom, granted Johnson a yearly pension of 300 pounds—a comfortable sum in those days. Johnson famously stated, “No man but a blockhead ever wrote, except for money,” and, indeed, from that moment forward he would be paid and paid well for his work. Now the projects were of his choosing and, in most instances the results were great. His Lives of the English Poets, including notable mini biographies of Milton, Dryden, and Pope, are a joy to read and worth any scholar’s time. Johnson’s preface to the plays of Shakespeare contains criticism that Shakespeareans—outside the mad world of post-modernism—still may read with profit.

In 1763, Boswell fulfilled his great ambition in meeting Johnson, and a friendship between the two developed. By 1764, the celebrated painter Sir Joshua Reynolds, another close friend, founded the “Club,” a gathering of British gentlemen that met regularly to talk of matters literary and moral. Besides Johnson and Boswell, it counted among its members Edmund Burke, Oliver Goldsmith, Charles Burney, Garrick, and, on occasion, Adam Smith. No minutes as such exist; what one wouldn’t give to have them. But one will find more than a taste of Johnson’s conversation in Boswell.

Johnson could be combative, sometimes physically. He fought off a gang of London ruffians until the night watch arrived and once floored a man with a rather choice weapon: a book. But he was generally fair. A dedicated Tory and Anglican, he nevertheless valued arch-Whig Burke’s friendship and believed that a few minutes’ conversation with the great parliamentarian would convince anyone of his genius. Johnson was also generous, granting room and board over a period of years in his lodgings to a gaggle of destitute characters. And nearing death, he refused opiates, so he might approach God with a clear mind.

What else can one say? If you haven’t read Johnson, read him. If you want a taste of his character, try Boswell. Once you have, you may find yourself agreeing with MP William Gerard Hamilton’s eulogy shortly after Johnson’s passing: “He has made a chasm which not only nothing can fill up, but which nothing has a tendency to fill up. Johnson is dead. Let us go to the next best: There is nobody; no man can be said to put you in mind of Johnson.”

(Credit to James E. Kiefer, John Wain, and Jackson Bate, whose biographical work provided the details for this essay.)