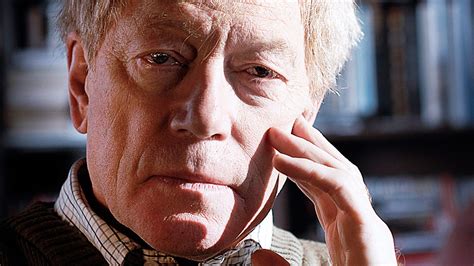

It’s hard to believe that Sir Roger Scruton passed from this life in January 2020, over three years ago. I hope no one will think me cynical for saying that such a span of time would extinguish the collective memory of many a public figure. Not of Scruton. His books continue to sell and, more important, to be read; his videos on YouTube still enlighten and please as powerfully as they ever did, even as the pleasure—mixed with the sad truth that Scruton is no longer with us—proves bittersweet. But at least for the minutes one watches him hold forth on an astonishing number of subjects including hunting, music, beauty, environmentalism, the Anglican church, or conservatism, he is alive again.

I suspect this is not exactly as Scruton would wish it. Few men seemed less interested in celebrity or, as was often the case with the trumped-up controversies that occasionally plagued him, notoriety. His passion was for tried-and-true practices and ideas: living the moral life, first and last, through inherited institutions and customs. A Roger Scruton Fan Club was never what he sought.

Nevertheless, he has such a club, but because Scruton’s writings and lectures are not for everybody, I’d like to think his fans are a discriminating lot. We can disagree with him, always civilly, when we think he has erred, as I do on certain points of religion, but even when we do, we know we’ve tussled with a mind that formulated positions carefully with the good as the primary goal.

Against the Tide, published last year by Bloomsbury Continuum, boasts the subtitle “The best of Roger Scruton’s columns, commentaries and criticism.” Admittedly, Scruton’s output was so great that any attempt to collect his “best” would amount to a thirteenth labor of Hercules. Granting that, I think Mark Dooley, the editor, has done a splendid job, offering readers not a taste but a feast of Sir Roger as a controversialist.

Like his books, Scruton’s short pieces cover a multitude of subjects comprising ones dealing with current issues, what Scruton called, “the work that must be done.” Writing with a clear prose, which I struggle to equal but rarely achieve, the collection with a section entitled “Who Am I?” Are the essays about him? Yes and no. Running approximately three pages each—they touch on his varied interests: wine, the Salisbury Review that he edited for years, Wagner’s Ring at the Proms, life on his farm, and his beloved Czechoslovakia (before and after communist rule).

As I’ve seen in so many of his books (News from Somewhere, Gentle Regrets, How To Think About the Planet, to pick three), his writings often move from the personal to the broadly topical. Yes, he was in Czechoslovakia, but he is not the subject; how the Czechs are dealing with their hard-won freedom is. And, given the title of the first section, this is a relief. Scruton interests me, but his thought interests me more. Because of that, this first section containing eight short essays or diary entries, tells us more about Scruton than any memoir (except perhaps Gentle Regrets) could.

The second section is “Who Are We?” For the most part, these essays, published in The Salisbury Review, The Wall Street Journal, The Times, The Guardian, and The New York Times, deal with British politics, with one exception, a piece on Donald Trump. At one point, Scruton describes Trump as “a politician who uses social media to bypass the realm of ideas entirely, addressing the sentiments of his followers without a filter of educated argument and with only a marginal interest in what anyone with a mind may have to say.” The ex-president’s recent snide comments about Gov. Ron DeSantis (or anyone who dares to oppose him) illustrate the point too well. That said, I think the most memorable essay of the lot is Scruton’s appreciation of Margaret Thatcher, all the more impressive because he was not a dyed-in-the-wool Thatcherite. But he knew she was a woman of intellect, principle, and courage, “the greatest woman in British politics since Queen Elizabeth I.”

The third section “Why the Left is Never Right” touches on human rights, the definition of fascism (the real definition, by the way), privilege, the “nanny” state, and “nanny” teachers. But my favorite is one that must be a shocker to some: “McCarthy was Right about the Red Menace.” The kiss of death in American politics is to call someone “McCarthyite.” Scruton has the courage to set the record straight. “The fact is,” he argues, “McCarthy was right. Maybe he went over the top; maybe it wasn’t necessary to point the finger quite so rapidly or in quite so many directions. But . . . he had taken on the greatest criminal conspiracy the world has ever known, and was all but weaponless before the secrecy and deception whereby it worked its grim enchantment.” That’s an observation scores of ex-New Dealers, left-leaning journalists, and Trotskyite academics should mull over long and hard.

So far, I’ve discussed three of the ten sections of Against the Tide, and I’ll leave it at that but for the ultimate grouping entitled “Annus Horriblilis and Last Words.” It’s heartbreaking to remember that Scruton had to bear more than one cross in his last year. Not surprisingly, one was the diagnosis of cancer; the other was the hatchet-job by an editor of The New Statesman. Scruton had written a very fine column on wine for them years before, so when the magazine asked for an interview, he obliged. The result was slander, a butchered version of Scruton’s actual words, as he says himself, “out-of-context remarks and downright fabrications.” A firestorm followed the “interview,” and its author crowed in a post about Scruton’s public disgrace, appending a picture of himself downing a bottle of wine to celebrate his “success.” Douglas Murray forced The New Statesman to release the transcript of the interview, which exonerated Scruton, and forced an apology. But, as Murray later commented, the journalist was not fired.

For all that, by December, Scruton spoke of the year as one of blessing: friends, such as Murray, who had come to his aid; doctors who had cared for him; a fall in public esteem in his own land balanced with acclaim in others (Poland, the Czech Republic). “Coming close to death,” he writes, “you begin to know what life means, and what it means is gratitude.” We live in an era of bogus heroes, whether ex-presidents, sitting presidents, tyrants, and rabble-rousers. It’s time to celebrate some truly heroic men. Roger Scruton, God rest his soul, is one of them.