Twenty-two years ago, a famous American philosopher died who had lived as a Catholic the last year of his life. Not so long ago, his name – Mortimer J. Adler – was synonymous with the “great books” approach to education he had pioneered with Robert Hutchins at the University of Chicago in the 1940s and 1950s. His edition of The Great Books of the Western World is still often seen if you survey the bookshelves of the homes and offices you visit.

Adler’s pedagogy, like his Aristotelian-Thomistic philosophy, was rejected by the academy he left in mid-career. He continued to edit, read, and discuss great books at seminars – like those he taught at the Aspen Institute – and to write scholarly books. But these were increasingly ignored, so in the late 1970s he took his case to general readers in an excellent memoir, Philosopher at Large: An Intellectual Autobiography, and books like Reforming Education and Aristotle for Everybody. Adler’s career began to revive.

But it was Bill Moyers’s several PBS specials with Adler – especially his “Six Great Ideas” seminar from the Aspen Institute in 1981 – that brought Adler back into the public eye. Adler capitalized on the attention with a series of readable books, winning him a new generation of readers. I was one of them. As a young philosophy professor teaching both St. Thomas and the great books, I regarded Adler with awe, knowing that he was a living link to Thomists like Jacques Maritain and Etienne Gilson, who had been his friends.

The first time I met Adler before a lecture at Mercer University Atlanta I mentioned my fondness for a novelist I was reading, the Australian Nobel Prize winner Patrick White. Adler immediately pulled out a notebook to write down his name and the novels I had mentioned. I was amazed that a philosopher of his stature would care about the opinions of a punky young professor! He encouraged me to stay in touch, and I did.

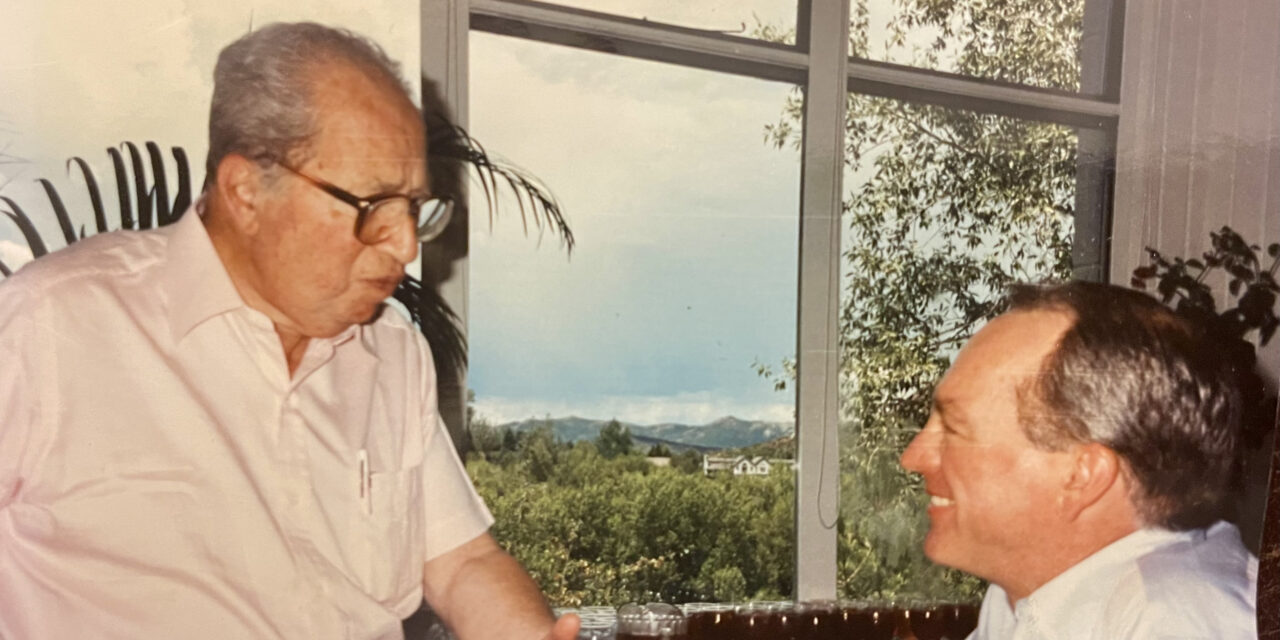

Some years later, Adler asked me to spend the first of three summers with him at the Aspen Institute assisting him in his seminars. I was the first Adler Fellow at the Aspen Institute and felt, well, honored. Afternoons were often spent smoking cigars and talking philosophy and religion (usually Catholicism). Talking to Mortimer was like talking to nobody else – his intellectual energy seemed to super-charge my mind, pushing me to think beyond the places where I had stopped before.

There was no question too dumb for Mortimer and no assertion so lame that it couldn’t be the source of another thirty minutes of conversation. During those summers in Aspen we talked for hours and never noticed the time passing, until his wife Caroline would come out the back door to remind us about dinner. (It was Adler before a lecture at Notre Dame for the American Maritain Society who told me that cigars never taste better than first thing in the morning.)

When I met Mortimer he had not yet suffered the heart condition that led him to his late-life conversion in 1986 to Christianity. When I asked him, at our first meeting in Atlanta, why his love for St. Thomas Aquinas had not led him into the Church, he replied, “Faith is a gift, and I have not received it.” Rather than ending the conversation, that turned out to be a darned good beginning.

He had been attracted to Catholicism for many years, but when he finally received “the gift of faith” he joined a different church. (Rumor has it that his wonderful – and ardently Episcopal – wife, Caroline, made sure of that.) Mortimer became a serious, church-attending Christian, albeit of the liberal variety, reading books by Bishop Spong and others. He once took me to an bookstore to buy me the latest title by Spong, but fortunately they were out.

The more we talked the more I realized Mortimer really wanted to be a Roman Catholic, but issues like abortion and the resistance of his family and friends were keeping him away. I tried to show him that his own Aristotelian-Thomistic metaphysics of act-potency led him to understand the necessity of protecting unborn life. But just at that moment, Mortimer would uncharacteristically mutter, “It’s all too complicated,” and change the subject. But I knew that he knew he was being inconsistent. I didn’t have to press him – because I knew he knew, and it was only a matter of time before he acquiesced.

At several of our seminars was the Catholic prelate of San Jose, Bishop Pierre DuMaine. The bishop and I would sometimes tag-team the philosopher on the Catholic Church, and we would all end up laughing about how Mortimer deflected the inevitable conclusion. As it turns out, Bishop DuMaine did not stop the Aspen conversations.

After Mortimer finally retired, and Caroline passed away, he moved to the West Coast to spend his final years. We kept in touch by phone, and I called him as soon as I heard from Bishop DuMaine that he had been received into the Catholic Church. To my ears, Mortimer sounded relieved and at peace that he had finally taken that step. The philosopher who had helped bring so many into the Church had himself finally arrived.

PS. Some years later I received a call from one of Mortimer’s sons asking if the story about their father’s conversion was true. I assured him that Bishop DuMaine witnessed it, and I had talked to both Mortimer and the Bishop to confirm it. His son graciously accepted my answer.

The picture above of Mortimer and me was taken during my first summer in Aspen.

♦ ♦ ♦

Five Books to Read by Mortimer J. Adler:

Aristotle for Everybody – The best introduction to Aristotle (especially his ethics) that I know.

Ten Philosophical Mistakes: Basic Errors in Modern Thought—How They Came About, Their Consequences, and How to Avoid Them – Here is everything you need to know about what is wrong with modern philosophy, written in a way you can understand.

The Angels and Us – One of my personal favorites. Adler has fun using St. Thomas’s treatise on angels to explain how the human mind works.

The Philosopher at Large: An Intellectual Autobiography – An important book to understand the course of American education, in addition to Adler’s own life.

The Difference of Man and the Difference It Makes (with an introduction by yours truly) – This, I think, is one of Adler’s most original contributions to philosophy: an argument for the immateriality of the intellect making human beings different in kind, not degree, from other animals.