Masterpiece Theatre really outdid itself this past week with its televised production of Mike Bartlett’s successful 2014 play “Charles III,” a fancy and fanciful dramatic musing on an imagined ascent to the throne of the current Prince of Wales. Those of us who had heard just enough about the play to feel sufficiently intrigued to tune in were in for a shock.

How so? For starters, the very idea is just a little scandalous. The play begins with the Queen Elizabeth II attending her own funeral—in her casket: a tricky business since at this writing she is still very much a living, breathing monarch. However, if you want a play about Charles III, Elizabeth must die, and, mark you, without the benefit of a touching deathbed scene. A chance missed? As may be, but “Thrift, Horatio, thrift!” A playwright has only so much space in which to cram his contemplated action, so from the opening the Queen is dead: Long live the King!

You may, dear reader, have noticed a couple of things about the preceding paragraph. First, it has a cliché or two. Well, so does Charles III, but more on that later. Second, it contains a quotation from Shakespeare, which, as far as I am aware, the program did not. But (and I’ll admit it took me a few minutes to catch it) the play itself mimics Shakespeare and does so shamelessly, with its court scenes in blank verse (the Bard’s chosen medium), its fair share of alliterative and rhetorical flourishes, and its frequent use of aside and soliloquy.

One might call the effort witty except in those numerous instances that it becomes embarrassing.

But on to the plot. Charles dutifully follows his mother’s casket into Westminster Abbey and, after moving to the narthex, delivers soliloquy number one dry-eyed. He’d always imagined, he says, ascending to the throne but in a completely different set of circumstances, the queen’s death in a helicopter crash, for example, after which he, a man in his prime, would take the throne and govern, well, vigorously.

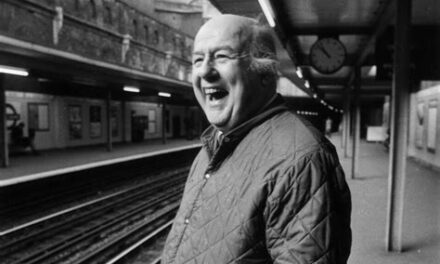

How to assert himself now that he’s an old man? The late Tim Piggott-Smith’s delivery is good, but I found it reminiscent of someone, chiefly Richard III with his frankly cynical speeches to the audience; of course, Charles is a far cry from that particular king, but I can’t shake the impression. Anyhow, as he reflects for our benefit, what is he to do that becomes the Great?

The answer surfaces in his first meeting with Prime Minister Tristan Evans (Adam James) of, by all appearances, a Labor Party that has somehow survived Jeremy Corbyn. As the British constitution stipulates, the king must sign any bill Parliament places before him, here an innocuous little piece of legislation giving the state unprecedented powers to regulate the press. (Oh how much Leftist politicians on both sides of the Atlantic think alike. Bartlett might have named Evans “Harry Reid.” That’s my aside.) King Charles—not yet crowned but King constitutionally—balks at the proposed infringement of British liberties, and a fracas follows.

It’s worth observing at this point that Charles III is in part a production of the BBC, and the BBC is not going to miss any opportunity to trash Margaret Thatcher. And so, Labor PM Evans launches into an impassioned diatribe on Charles’s refusal to sign. Didn’t Elizabeth comply with all sorts of Thatcher-inspired bills she loathed? Didn’t she sadly watch the dismantling of the traditionally union-controlled economy? (Another aside: “traditionally” as in fifteen years old, going all the way back to Harold Wilson; but fifteen years is as good as fifteen centuries to the Left.) Didn’t she stoically witness the disappearance of Britain in the blight of “Reaganism and Thatcherism”? Yes, Charles agrees, but he will not sign.

To be sure, there’s a smidgen of St. Thomas More in the principled stance and perhaps a bit of Luther too. But one could do worse, especially since there are plays written about both men.

All told, a constitutional crisis is bubbling to the surface, one even the Conservatives don’t want, but that’s nothing compared to what’s happening at Buckingham Palace. Camilla (Margot Leicester) counsels a more or less stiff upper lip. Weak William (Oliver Chris) can do little but remind every one of the obvious, that his father is the king, while Kate (Charlotte Riley), his wife and everybody’s sweetheart, reveals via soliloquy her inner Lady Macbeth, unsexing herself by never letting a good crisis go to waste. Her goal is to spur hubby into forcing Charles’s abdication and taking the throne for himself—while, as a matter of course, gaining a crown for herself. Even the ghost of Princess Di (Katie Brayben) gets into this royal maelstrom, materializing in dusky rooms to promise first Charles and then William greatness beyond all historical precedent, a future “star of England,” as somebody might say.

Playing second fiddle and, hence, by definition, in the background, is Prince Harry (Richard Goulding). But he will strut his hour on the stage, which, so far as I can see, is that of a scruffy Hamlet, ambivalent about who he is and what to do. His solution is to fall in love at first sight with a black, lower-class, anti-monarchist Ophelia named Jess (Tamara Lawrance)—an everything-but-the-kitchen-sink love affair (or almost everything; she’s not bi-sexual) that has “star-crossed written all over it,” which peppers Romeo and Juliet into the dramatic stew. She resists, but he must have her. And even though she once posed pornographically for somebody or other—a blot on her reputation picked up by the tabloids, the King gives his blessing and assures the lovers that even porn cannot supply sufficient grounds for limiting freedom of the press.

I mentioned clichés, didn’t I? Score it as you will, I think there are about a half dozen by now.

But back to the constitutional crisis. Charles, inspired rather cagily by the Conservative opposition leader Mrs. Stevens (Prianga Burford), a woman of tawny complexion (an Indian, a Muslim, or another cliché?), dissolves Parliament, and all hell breaks loose with rioting in the streets and tanks confronting the mob before the palace. What to do, indeed?

The deus ex machina squeakily lowers Kate and a Machiavellian minister to pressure William into saving the monarchy by forcing Charles’s abdication in a rigged press conference. The writ of abdication is finally signed by an alternately angry and tearful Charles—sounding for all the world like Richard II in Acts III and IV of Shakespeare’s play—and the coronation finally takes place though not quite as imagined in the beginning. The drama is thick until the bitter end when it reaches its pitch as the Archbishop of Canterbury (John Shrapnel)—who was not, I’m relieved to say, an imam—ceremoniously approaches William, only to be waylaid by Charles who takes the hollow crown and places it on his son’s head before rushing off and shedding the tears he could not manage for his mother.

T. S. Eliot writes, “O O O O That Shakespeherean rag— / It’s so elegant / So intelligent.” And, no mistake, the critics have judged Charles III a hit. Let it be, but for me, the play sinks of its own cleverness and drowns in a flood of clichés. Could it be it was designed from start to finish as a farce? Might a second viewing prove entertaining? Alas, no. Like Fabian in Twelfth Night, I’m moved to conclude, “If this were played upon a stage now, I could / condemn it as an improbable fiction.”