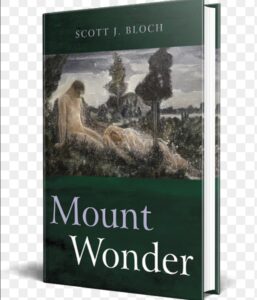

Mount Wonder

by Scott J. Bloch

Resource Publications

450 pages

Proust on the Plains

The setting is the late 1970s at the University of Kansas in Lawrence, a town that stands in relation to the rest of Kansas much as Austin does to Texas. The story reminds us that our best and oldest friends tend to be those we know from college. For the first time in our lives, friendship depends not on the happenstances of propinquity but on shared cultural references—cultural both high and low. History-major types meet history-major types. Bob Dylan enthusiasts find other Bob Dylan enthusiasts.

The friends in Mount Wonder share references that include: Homer, Plato, Dante, Donne, Dostoevsky, and T. S. Eliot (and, chopped more finely, Madam Sosostris and Hieronymo), and (more unusually) St. Benedict, St. Thomas More, and G. K. Chesterton (perhaps a future saint, the first to be hilarious). And Steely Dan as well.

They are classmates in a team-taught Great Books–style course that has recently come under administrative scrutiny. The problem: in guiding the students on their quest for truth and beauty, the teachers may have been suggesting that there really is such a thing as truth. Some of the kids are finding that truth in the One True Catholic and Apostolic Church. Among them is the protagonist, Bernard, a Jewish Los Angeleno who has picked up the nickname G. K.

Taking clear inspiration from the original G.K., Scott Bloch gives himself leave for the robustious rollicking of the Chesterton of the comic novels. I was particularly reminded of Manalive, with its houseful of eccentric young people. Bloch’s Bernard discovers the controversial course not as a truth seeker but as a hired informer for the administration, who then becomes a kind of double agent for the Great Books side. One might, then, be put in mind of The Man Who Was Thursday. And we are certainly put in mind of the topsy-turvydom of our own time, when we need no Chesterton to point out the paradoxes. The paradoxes now present themselves candidly and without abashment.

The teachers and students are brought before a hearing, which gives Bloch, a Washington attorney, the opportunity for a couple of courtroom scenes. In one, a teacher reveals the true secret intent of the course: to show students that there may be ways to escape the constraints of a conventional life, and that freedom from convention just might lie in traditional conventions. As someone puts it: “To question authority, it turns out, is to question modernity.” As Chesterton put it: “Men invent new ideals because they dare not attempt old ideals. They look forward with enthusiasm, because they are afraid to look back.”

The students are urged to be ever daring.

Bloch is an inveterate punster who gives us far more smiles than groans. My own favorites are the chapter titles “Descartes Before the Whores” and “Tom Waites for No Man.” And the name of the house pet: Phaedo.

He also has a knack for descriptions that make his scenes both visible and risible:

Of an administrator: “His upper body was overlong, giving him the appearance of a Minotaur.”

Of the vice chancellor: “His trim moustache seemed to have its own life-support system, like a dog’s tail.”

A canon lawyer from Rome who defends the students in the hearing “had a face like a library: familiar and formal at once, inviting and vast.”

On the arrival of an unexpected visitor from L.A.: “There was my father, Norm Kennisbawn, standing before the statue of the Virgin Mary, studying it as if it were a piece of inscrutable pop art.”

Bloch also gives himself the license of Proust by telling us frankly that the story is close enough to his own story to contain the distortions of memory. In italicized“Interludes,” he speaks as a searcher of lost time rather than as the lost youth of that time, as in this nice passage:

“In memory, we find reassurance as a child finds reassurance in the retelling of stories. Hansel will try again to find the way home, following breadcrumbs along the path; Peter Rabbit will somehow manage to learn his lesson. In a retelling, I might become G. K. Chesterton, the jolly warrior for civilization’s lost verities.”

As someone who went to college just four years later and just a few miles to the east in Missouri (and who knows Lawrence, Kansas, well), I can attest that his memory of his setting is not at all distorted. Like a film on actual 35mm film, the novel is a faithful documentation of the world, and yet it gives the world its own texture. Like film and unlike digital, it has its own place in space and time

________

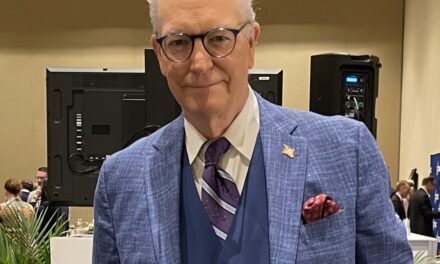

Stephen Binns is an editor at the Smithsonian. His writing has been accepted by the Atlantic, the New Yorker, the National Catholic Reporter, First Things, and the Journal of Classical Poets. He is currently at work on a terza rima translation of the Divine Comedy, somewhat imagined as if Shakespeare had rewritten the Dante, and a terza rimatranslation of the Aeneid, somewhat imagined as if Dante had rewritten the Virgil.