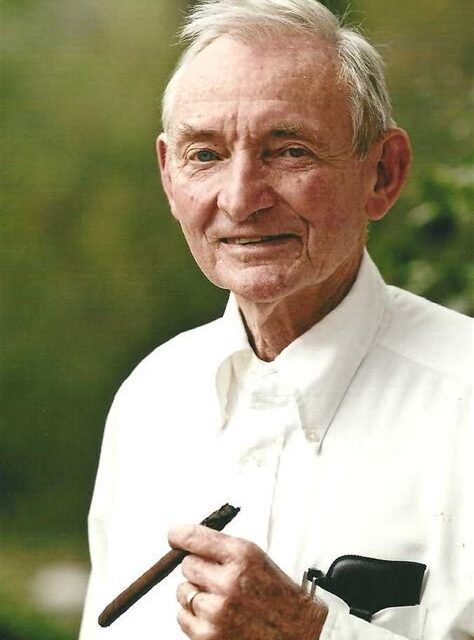

Readers of The Christian Review may already be familiar with the name Marion Montgomery (1925-2011). During his 30 years as a professor at the University of Georgia, Montgomery published articles regularly in Modern Age, Hillsdale Review, This World, Chronicles, and Crisis Magazine. But the growth of Montgomery’s reputation was spurred greatly by the publication in the early 1980s of his massive trilogy, The Prophetic Poet and the Spirit of the Age. Mentioning the trilogy by its proper title can draw a blank stare, while the catchy titles of the individual volumes — Why Flannery O’Connor Stayed Home, Why Poe Drank Liquor, and Why Hawthorne Was Melancholy — are usually recognized by those familiar with literary history and criticism.

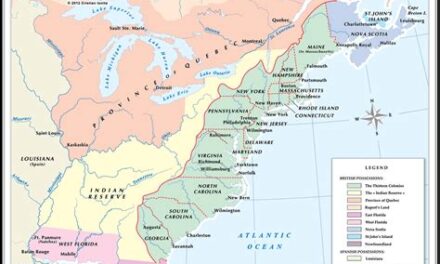

Not recognizing the actual title of the trilogy, unfortunately, has obscured the real intent and significance of his achievement. Certainly these volumes consider O’Connor, Poe, and Hawthorne, but the whole trilogy, as its title indicates, is after much more. Its 1,400 pages contain nothing less than a “prophetic” Thomistic critique of the American “popular spirit,” as it has evolved from the New England Puritans and Transcendentalists to the present legion of modernists.

Montgomery writes in the Preface:

We shall consider whether, in consequence of the triumph of opinion over reasoned judgment, a consequence of ideological illusions practiced upon the community of man this past four or five hundred years in the interest of gathering power over nature and man — the popular spirit of our age has reached a condition whereby each man must be his own ideologue; whether indeed he insists upon being so as a “natural right”; and whether there is rescue from the isolation of that position.

That such a project is unique in American studies, cultural and literary criticism, as well as in Thomism, makes Montgomery’s trilogy distinctive; that he brings it off in a compelling fashion earns The Prophetic Poet and the Spirit of the Age pride of place on bookshelves next to Cornelio Fabro’s God in Exile, Paul Johnson’s Modern Times, Friedrich Heer’s Intellectual History of Europe, and the multi-volume, The Glory of the Lord — A Theological Aesthetics by Han Urs von Balthasar.

These books share the use of Christian realism in diagnosing the rise and fall of Western culture, its causes and its deleterious effects. This parallel with works whose foci are European also indicates the gap that Montgomery has filled for his audience: a critical reading of American culture, founded upon the Catholic realism of classical and Christian Europe, focusing on the specific spiritual development of America. Montgomery was a scholar who, beyond being deeply read in the classics, clipped his daily newspaper, a habit which provided the trilogy a richness of illustrative detail normally not found in books of similar conceptual reach.

The trilogy attests to Thomism’s continuing vitality: Montgomery has brought St. Thomas to America like no one else before him. In doing so, he has provided an entree into our own inherited past. By providing a map to the spiritual terrain of American literature, Montgomery makes it possible to rediscover the American classics — Hawthorne, Emerson, Poe, James, Pound, Eliot, Faulkner, Nathaniel West —in the light of the Anglo-European Catholic culture to which many Catholics have for years felt bound. For this, all the people of faith in America owe a lot to the legacy of Montgomery.

Like his close friend Flannery O’Connor, whose witness inspired the trilogy, Montgomery speaks with a distinctly Catholic voice from the heartland of the Protestant South (Marion and his wife, Dot, also deceased, belonged to an Anglo-Catholic church). Widespread recognition of O’Connor’s writing came slowly because she “stayed home.” When Montgomery said of O’Connor, “Being a Southerner does not in fact set her in a separate world,” he spoke also of himself.

Slowly, the worth of his contribution was recognized. Gerhart Niemeyer has paid him tribute in the Center Journal (“Why Marion Montgomery Has to Ramble,” Spring 1985). Christendom College held a major symposium on the trilogy, the papers from which were subsequently published in The Hillsdale Review (Spring/Summer 1986). Regular invitations to lecture around the country soon followed. His commentators agree that Montgomery’s voice is not just another in the chorus decrying the woes of the modern world. Montgomery breaks through the impasse created by mere angry protest and supplies what Niemeyer calls a “spiritual therapy.” It is therapy on a high intellectual and broad historical plane. Note Montgomery’s comment on O’Connor’s view of Southern manners:

Let us say that manners are what we discover in community as an aid to the individual member in those moments when his good will falters and best thought weakens. It is the poetry of being beyond the literal words or gestures that embody manners. Manners let the soul catch its breath in the difficult journey of the world where at every moment one may lead himself astray…. To deliberately abandon or reject that deportment of being in nature which we call manners, which order our fallible inclinations, is to willfully enter the jungle, no matter how attractively chrome-plated or path-paved that jungle.

Montgomery moves back and forth between the worlds of the philosopher and the poet with ease, saying he falls “somewhere between Faulkner’s poet and Plato’s philosopher, committed at times to metaphor, at other times to definition.” His facility at connecting these different worlds of discourse seems so natural and unforced that you are left wondering why this kind of “undulating conversation,” as Niemeyer describes the trilogy, has fallen into disfavor. Montgomery’s courage to move beyond the accepted limits of literary criticism, without descending into the murky depths of deconstruction, reminds one that Samuel Johnson once called literary criticism “good talk about books.”

Montgomery’s ability and willingness to undertake such a project naturally provokes interest in his background. He had the good fortune to study English literature at the University of Georgia in the late 1940s, after his military service. Those who are familiar with the history of American letters will remember that Georgia had enjoyed close ties to Vanderbilt’s “Fugitives and Agrarians“ since the 1930s. The legacy of Donald Davidson, Allen Tate, John Crowe Ransom, and Andrew Lytle was strongly represented on the Georgia faculty by William Wallace Davidson (Donald’s brother), John Donald Wade (founder of The Georgia Review), and Robert Hunter West, who became Montgomery’s early mentor and lifelong friend. Thus situated, Montgomery was near the center of one of this country’s most important intellectual and literary circles (witness the influence of Cleanth Brooks and Robert Penn Warren while on the English faculty at Yale in the 1950s). He enjoyed personal friendships with many of them. After Montgomery’s death, I had the privilege of looking through his private papers where I found several drawers of file folders containing all his correspondence, including several handwritten letters from Flannery O’Connor that have never been published.

While a graduate student, Montgomery was introduced not only to the classicism, literary discipline, and cultural criticism of the Fugitive-Agrarian movement but was also introduced to Aquinas, Dante, the Neo-Thomists, and other Catholic authors. Montgomery and his wife Dot met weekly for several years with other couples from the department to study these texts in a group they called “St. Thomas and Rabbit Hunters.” Reading St. Thomas in the context of his Fugitive-Agrarian education, Montgomery began to see the similarity of their concern for the recovery of our “ordinate relation” to being. Thomas’s metaphysics of esse, “a sort of static energy in virtue of which the being actually is, or exists,” established for him a larger context in which to pursue Fugitive-Agrarian concerns.

Whereas some readers are tempted to view Montgomery as the last of the Fugitive-Agrarians, he described himself as an “enlarger upon them.” The reason for his continued interest in Fugitive-Agrarian literature and ideas can be understood from a statement made by one of its early leaders, Stark Young: “We defend qualities not because they belong to the South, but because the South belongs to them.” These qualities include an affirmation of history and tradition, of the family and community, a distrust of urbanization and the claims of technology, the social role of the poet, and the universal need of a religious faith.

Thus, Montgomery’s ties to the Fugitive-Agrarian tradition are far from sentimental or reactionary. A taste for Tara, mint juleps, and ante-bellum gowns only draw his fire: “History, when it is preserved in its viable form, is in people, not in things, in clothes or buildings on which attention is focused by idle holiday curiosity or with a vague sense of guilt for the neglect of heritage.” What Montgomery finds prophetic in the writings of Davidson, Tate, and Ransom, he also found in Thomas Aquinas and Solzhenitsyn, both of whom he has had the good humor to describe as “Southerners.”

Why? Because together they have sought to protect being from those who would deny its otherness, the integrity of its existence apart from the mind, and to establish a genuine stewardship of creation grounded in a well-ordered love of what is given. In order to explain the “spiritual dislocations” that have perverted our relationship to being, Montgomery, following Eric Voegelin, employs the names of the ancient heretics, primarily the Gnostics and Manicheans. The bulk of his trilogy traces the American versions of these two heresies, each leading from a metaphysical denial of being to a denial of the human body and its role in the order of knowledge and the formation of virtue. These heresies deny the necessary function of the senses as instruments of knowledge and the necessity that virtue be embodied in actions repeated over time.

It is not the scope of these three volumes alone that makes them difficult to describe in a short space. If Montgomery were busy running his authors like grist through an ideological mill toward a pre-established outcome, summarization would be easy. Montgomery, however, loves his subjects too much to treat them as grist. He turns them round and round for his reader’s gaze. His generous scrupulousness becomes a source of enjoyment; it provides the unexpected turn, the personal aside, the unforeseen comparison, and, as I have said, the embodiment of his analysis in concrete detail.

For example, in his discussion of “The New Sentimentality: Man as Wind-Up Mouse,” Montgomery brilliantly connects the best-known character in O’Connor’s fiction, the Misfit (from “A Good Man Is Hard to Find”), with Hannah Arendt’s portrait of Adolf Eichmann — who represents “the banality of evil”— along with Charles Manson, the Jonestown massacre, and, of all things, transactional analysis. “A little time,” he writes, “a little distance, and a magnitude of effect in time and place make for dramatic speculation on the question of evil. But the same questions, seen in our immediate present, lacking the authority of history’s spectacles, those large accomplished effects, are likely to strike one as merely trivial.”

Chapter after chapter (and it is no accident that each volume contains a Dantean 31) of such counterpoint between idea and historical consequence may at first seem like mere “rambling,” until one realizes how used to the constricted range of academic writing we have become in our reading habits. Don’t be fooled by the casual, almost offhand tone of his writing. Montgomery has brought his art to these books, in addition to this prudence and his speculative insight (theoria). As he told me, you have “got to make the watch before you can wind it,” to which we might add, “and tell the time.”

The trilogy is packed with major and minor characters. Aquinas, Voegelin, Eliot, the Fugitive-Agrarians, all play an equally important role in Montgomery’s argument, second only to Flannery O’Connor. Dante, Eliade, Faulkner, Maritain, Nietzsche, and Teilhard de Chardin are discussed throughout the O’Connor volume, while Bergson, Baudelaire, Heidegger, Pascal, and Sartre surround the discussion of Poe. The treatment of Hawthorne’s melancholy takes the reader backwards to John Locke, Jonathan Edwards, and John Winthrop, and forward to George Santayana, Nathaniel West, and Henry James. Here we also receive the answer to O’Connor’s question,” Why did Henry James like England better than America?” Montgomery notes that “there [James] discovers a devotion to form still pervasive in the rarer reaches of the intellectual community; it is with subtle English manners, examined as an outsider, that James is concerned . . . But one does not find James concerned with the mystery upon which Miss O’Connor found manners to depend.”

This concern for mystery takes us to the heart of Montgomery’s trilogy. It is a mystery witnessed to by the silence of Aquinas, the “Ash Wednesday” of Eliot, the grotesques of O’Connor; a mystery sinned against by James’s aestheticism, by Poe’s Manichean denial of the body, by Emerson’s attempt to restructure being; and by Hawthorne’s inability to break free from idealism. Mystery, as Jacques Maritain taught, can be approached, though not encompassed, by thought. A mystery is supra-rational, but not irrational. Montgomery takes the reader toward what can be known and felt of the mystery that expresses itself in and through what Voegelin calls the “in-between” nature of human existence. Gnosticism and Manicheism both seek to escape the “tensional” nature of life; they fail to see the esse (thatness) behind the ens (what-ness).

Metaphysically confused from the start, modern heretics have gradually reduced all of creation to mere products of thought, of consciousness. Thus established as what Voegelin calls “gnostic directors of being,” they void the problem of evil and pursue in this world the perfect beatitude they deny in the next. Montgomery locates the entry point of this millennialist utilitarianism in the Puritan mind, represented in Winthrop’s image of “a shining city on the Hill.” Montgomery observes: “One may discover here a shift from St. Augustine’s careful concern for the difference between the City of Man and the City of God, a shift which in its subsequent consequences following the Plymouth landing has secularizing consequences beyond Winthrop’s anticipations.”

Indeed, for Montgomery it was Emerson who translated this Gnostic Puritanism into a full-blown secular program for the restructuring of human existence, “a closed Eden,” within the individual human mind. Commenting on the hostile reception given to Solzhenitsyn’s speech at Harvard, Montgomery writes: “Emerson, we must insist, is a considerable force in that establishment [Harvard] —a Gnostic thinker whose influence we have yet to overcome.” One only has to listen to the gurus of the “New Age” telling us that we “can create our own reality” to realize how strongly that influence continues to be felt.

Hawthorne, living down the road from Emerson in Salem, was not taken in by the growing influence of the latter’s abstract optimism, detached as it was from an immediate encounter with the world of particularity. Hawthorne preferred the surroundings of his “town pump” to Emerson’s creation of the “New Man” in the utopian “city on the hill.” But Hawthorne failed in his prophetic attempt, through his adoption of allegory, to escape the growing narcissistic mood and to recover his love for the world as given to the senses.

Poe, however, can hardly be said to have attempted a step in the right direction. He explicitly rejected the manipulative empiricism of the eighteenth century, particularly its nadir in utilitarianism. But “the anemic, lost soul in that new world dreamed into being since the Enlightenment seems indispensable to Poe.” Instead of recovering the vitality of the world, Poe sought refuge in a supremacy of the intellect that excludes the outer world altogether. Poe reversed the direction of Locke’s epistemology: instead of a tabula rasa receiving a world of perceptual impressions, Poe’s mind created the world on its own; his symbolism operates as a mental mirror rather than a window.

Montgomery describes Poe as countering the absurdity of the Enlightenment by ushering in the Absurd — “He may even be called obscene, practicing a sort of necrophilia upon the dead body of the world.” Thus, his status in the trilogy as a “prophetic poet” seems ironic compared to Hawthorne, and certainly compared to O’Connor. The vision that Montgomery finds in Poe, one that strains toward “a spot of time, a still point, a moment of grace,” gazed, nevertheless, more in the direction of the deified Self, in the direction of Heideggerian and Sartrean existentialism, rather than toward the prophetic recovery of “old but forgotten things.”

Readers of the trilogy will immediately notice that Montgomery regards Flannery O’Connor as the prophetic poet of twentieth-century American letters. Montgomery’s treatment makes this a highly plausible claim. Whether the literary establishment will listen is another matter. The popular “Catholic” novelist Brian Moore, reviewing the newly issued Library of American edition of O’Connor’s works (New York Times Book Review, August 21, 1988), went out of his way to call her work “not great.” Not only was his remark inappropriate on such an occasion but it also betrayed, along with a touch of envy, a “we’re-beyond- this-kind-of- thing” attitude toward O’Connor’s straightforward Catholic orthodoxy.

If you haven’t read O’Connor, Montgomery will send you in search of her collected works; if you have read O’Connor, you will want to begin re-reading. Montgomery knew Miss O’Connor well. They exchanged letters; she praised his fiction. After her death, Montgomery spent many hours in her library at Georgia College in Milledgeville reading the books she had collected and noting her comments and underscorings. In Montgomery’s hands Flannery O’Connor emerges as both a “major” writer and critic, a “realist of distances” whose philosophical and spiritual understanding was not limited, but rather enlarged, by both her Southernness and her Catholicism.

As Montgomery explains in his chapter entitled “Getting to Know Haze Motes: Nietzsche as a Country Boy,” it is to O’Connor’s Wise Blood we should look for an explanation of why existentialism was so easily assimilated in American high and low culture: “You don’t have to have attended the Sorbonne to be an existentialist.” Next to her collected essays, Mystery and Manners, and her letters, The Habit of Being, there is no better place to discover the remarkable mind behind the fiction than in Why Flannery O’Connor Stayed Home.

Long before he wrote his trilogy, Marion Montgomery had established his reputation as a literary critic and as a novelist and a poet with four novels and three books of poetry to his credit. In 1974 his last novel, Fugitive, was published by Harper and Row. His first books of criticism appeared in 1970: Ezra Pound: A Critical Essay and T.S. Eliot: An Essay on the American Magus, for which Allen Tate wrote on the jacket, “I have learned for the first time how to read ‘Ash Wednesday’ and ‘Prufrock.’” These were followed by The Reflective Journey Toward Order: Essays on Dante, Wordsworth, Eliot, and Others (1973), which Montgomery considers a prelude to the trilogy, and a second study of Eliot, Eliot’s Reflective Journey to the Garden (1978). Then came The Prophetic Poet and the Spirit of the Age (1980-84), followed in 1987 by a book which could be called its “afterword,” Possum and Other Receipts for the Recovery of “Southern” Being, resulting from the invitation to deliver the thirtieth Lamar Memorial Lectures at Mercer University.

For those who are interested in a shorter, more accessible introduction to Montgomery, I recommend starting with his forthcoming Concerning Virtue and Other Modern Shadows of Turning: Preliminary Agitations. Based upon a series of 1982 lectures sponsored by the Intercollegiate Studies Institute, Concerning Virtue discusses the Socratic question of whether virtue can be taught, and in the process restates many of the major themes found in the Trilogy. This book will appeal to those who are put off by the rather dense, intricate pattern of intellectual cross-references in the trilogy, in Possum, and in The Reflective Journey Towards Order. Like Possum, Concerning Virtue extends the argument of the trilogy even further into the fabric of American life, featuring as its centerpiece a provocative expose of “Ralph Nader as Gnostic Puritan.”

Montgomery is far from finished. What would be the fitting finale for most scholars, the trilogy appears to be only a deep gathering of breath, but one many of us will be studying for years. Closely upon the heels of Concerning Virtue will follow Montgomery’s Words, Words, Words, based on the Younts lectures given at Erskine College, in which he enters the fray, created by Allan Bloom and E.D. Hirsch, over the deterioration of the liberal arts curriculum and the responsibility of the university to society.

In the last fifteen years of Montgomery’s life, books poured out of him, starting with The Trouble with You Interleckchuls (1988); followed by Liberal Arts and Community (1990); Men I Have Chosen for Fathers: Literary and Philosophical Passages (1990); Romantic Confusions of the Good (1997), dedicated, I admit with gratitude, to me; Concerning Intellectual Philandering: Poets and Philosophers, Priests and Politicians (1998); The Truth of Things: Liberal Arts and the Recovery of Reality; (1999) Steps Towards Restoration: The Consequences of Richard Weaver’s Ideas (2000); Making: The Proper Habit of Our Being (2000); Romancing Reality: Homo Viator & Scandal Called Beauty (2002); Eudora Welty and Walker Percy: The Concept of Home in Their Lives and Literature (2003); John Crowe Ransom and Allen Tate: At Odds About the Ends of Literature and the Mystery of Nature (2003); On Matters Southern: Essays About Literature and Culture 1964-2000 (2005); With Walker Percy at the Tupperware Party: In Company with T.S. Eliot, Flannery O’Connor, and Others (2006); and Hillbilly Thomist: Flannery O’Connor, St. Thomas, and the Limits of Art (2006).

The work of Marion Montgomery still awaits its proper recognition. There are many scholars and writers who speak with reverence of Montgomery, both the man and the work, but as yet no one has come forth to attempt a synthetic, critical account of his unique contribution to American letters.

Nearly forty years ago Marion Montgomery published a verse that has subsequently proved prophetic:

In February Freeze

I am beginning to think of the possibility of song:

These too froward flowers in a cold abstraction

have burst grossly outward.

Black tissues will grey in a slough of March’s ease-

ful deceptions.

Still, I am beginning to think of the possibility of

singing:

These dead flowers’ risk, vision in praise of possible

song.

[from The Gull and Other Georgia Scenes, 1969]

(An earlier version of this essay appeared in Crisis Magazine, May 1, 1996.)