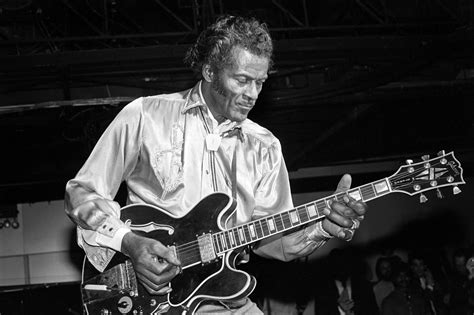

Chuck Berry passed from this life on March 18th, and if I had nothing to say about it, well, I ask you, does the world really need another Chuck Berry eulogy? Besides, the order of praise was predictable. He was a “pioneer of rock ’n’ roll” (New York Daily News), “rock ’n’ roll’s first guitar hero and poet” (the Guardian), the first “to define rock ’n’ roll’s potential and attitude” (New York Times), “one of that exclusive group who took rhythm and blues from its black roots” to mainstream (BBC). All of which is to say Chuck Berry was “great.”

Indeed, “great” is the word of choice whenever a rocker—usually one from the sixties or seventies—departs this world, just as it’s the word, explicit or implicit, used to describe rockers who have not yet cemented their claim to fame by dying. Glenn Frey was “the great Glenn Frey”; so was Michael Jackson. Elvis? Not only was he great, he was the “king,” or, as Kurt Russell once put it on a brief tribute to Presley on Turner Classic Movies, “the singer” of the twentieth century.

I once read a critic and, I suppose, rock historian, praise Brian Wilson—who, so far, has escaped the Grim Reaper—as “our Mozart,” which is just another way labeling him the “great” Brian Wilson.

There’s no doubt about it: rock is omnipresent. It’s virtually impossible for one to go to a grocery store, sit in a restaurant, turn on a radio program (one, mind you, ostensibly dedicated to news or opinion), or, in many instances, attend church without having one’s ears A-bombed by the strains of what is the music of the mainstream, the pith and marrow of our culture. The old Huntley-Brinkley Report on NBC used to conclude majestically with the opening bars of the second movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony; today, if the show still existed, it would likely end with the cacophony of generic heavy-metal.

Musically speaking, rock has two notable virtues, namely, energy and rhythm: one feeds the other. But beyond that and in spite of extravagant claims of rocker X’s being “our Mozart,” rock was, is, and, as long as it endures, ever shall be popular music, first and foremost adolescent entertainment of the moment. Let the Rock ’n’ roll Hall of Fame anoint whomever it chooses with immortality, most rockers fade quickly from the scene. Does anyone remember Question Mark and the Mysterians or The Music Machine? (Alas, I do.)

Apparently, only the relatively few “greats” manage a real place in memory; for the others, the glory becomes bleached-out before it has time to truly fade. But the forgotten groups still have their songs. Mention “Ninety-six Tears” or “Little Bit of Soul” to anyone thirteen or older in 1965, and you’ll likely see a smile of recognition. Play them at a sports gathering, and you’ll see thousands bumping if not grinding to the beat—too many of them in their sixties.

For us, the ones who for good or ill, remember Chuck Berry, a worthless mid-sixties tune is a trip down memory lane. And I do understand; I enjoyed a lot of the music of my teens and twenties and, truth be known, of later years; I remember not only a lot of songs I enjoyed, but many I thoroughly hated. Allowing that, I also contend with absolute conviction that the world would be a better place if Chuck Berry, Elvis, Little Richard, and every Commando of the British Invasion had never lived.

Why do I say that? Consider: If bad money drives out the good (Gresham’s Law), we may assume bad music has a similar effect on the good music. When Professor Allan Bloom called rock the real junk food of the young, he got it right enough, but the problem runs deeper than that: rock now is the junk food of the aged, old fogies, or “my generation” as The Who would have it. Adolescent music creates—at least, all too often—permanent adolescents.

All of those obituaries praising Chuck Berry weren’t written for eighteen-year-olds, not by a long shot. The journalists that wrote them were betting on the collective bereavement of a generation, one that should have greeted the event with a nod of vague remembrance before proceeding to matters of real weight. But obit writers knew their audience and its largely uncritical acceptance of the basic claim: Chuck Berry was “great.”

Not too long ago, Peter Hitchens quipped that if the old proverb (attributed to Clemenceau) about all twenty-year-olds’ being anarchists and all adults’ being conservatives is true, why are sixty-year-olds going to Rolling Stones’ concerts in tee-shirts? Why, indeed? As a cultural phenomenon, this is not simply depressing; it’s pathetic. My parents thought Elvis was patently talentless. They expected singers to have certain gifts: range, timbre, control, and phrasing. To them, the “King’s” excessive vibrato in “Love Me Tender” was a dead give-away that he was lacking in the fundamentals.

But Elvis prevailed—and why? He was sexy and rebellious—and he made both look easy. Not everybody can claim that, but his rise, along with Chuck Berry’s, sounded the death knell of an older popular music—of Artie Shaw and Ella Fitzgerald—that could claim, sometimes tenuously, a tradition not far removed from Mozart. I know that my parents, who loved to dance, expected the music of the forties and fifties to be rhythmic and tuneful; they also expected much more and knew when they weren’t getting what they, with generations before them, had been culturally educated to hear. Before Elvis and Chuck, a higher form of music, even if heard only during the credits of the Huntley-Brinkley Report, was recognizably the stuff popular music was made of; for some, it was the clarion call of civilization itself.

For too many of my generation, however, listening to great music or even good music remains an unknown experience. It’s one thing to say that they’ve forgotten the rare moments in school when they heard a small sampling of a symphony or concerto. It’s quite another that the “culture” of rock has so dominated their souls that they can’t imagine music’s offering more. It’s no surprise, then, that critics and their public feel obligated to lament the passing of an Elvis, a John Lennon, and a Chuck Berry in a way that past generations marked the deaths of Tchaikovsky, Haydn, and Handel, in other words, of true geniuses.

I could live with rock music, if its votaries would tone down their fulsome praise a few notches and give better music a chance. But for too long now “genius” and “great” have been bandied about so carelessly that people don’t know what the words mean. This ignorance has resulted in the death of a generation’s sensibilities. Is it any wonder that their children and children’s children have embraced barbarism?

This is a very good article, thank you for sharing it. I agree with you on many of your points. I suppose one of the greatest evils that have come out of the 60’s is the adolescent attitude towards sex and drugs and women. After saying that, even though I am 68, I still like some heavy metal from time to time. However, I know that it is mindless and just fun, not great music.

All one has to do is to read up on the lives of ‘rock and roller’ to see how it is a dead end for most of them.

When young, I last some friend to drugs, that taught me to stay clear of them.

Thanks for your insights.

There’s a whole lot to like about a whole lot of music. From Bach to Borodin to the Beatles; Dvorak to Dorsey to Dylan; Elgar to the Eagles to the Eurythmics; Joplin to Joel to Janos Starker; Mozart to Merle Haggard to Joni Mitchell; Zubin Mehta to Led Zeppelin, and, yes, the Rolling Stones to Rachmaninoff. Someone might disagree, but I won’t lose sleep over it.

Each generation glorifies the music of their youth and berates the next generations music. At the same time they condemn the music of their parents generation. Take this article with a grain of salt.

Great only means “we like you” or “we agree with your politics”. Nothing to get hung about.