“Heard Melodies Are Sweet, but Those Unheard Are Sweeter,” wrote John Keats in his famous “Ode to a Grecian Urn.” This explains the pleasure of memories, especially those of a Christmas sixty years ago.

My family lived in Prairie Village, a suburb of Kansas City, in a modest ranch style house. My father, an airline pilot for Braniff, was a lean and handsome Texan who carried on his face traces of sadness from his fifty B-24 missions flown out of Italy over Eastern Europe during WWII.

I didn’t know then he would have rather owned a ranch, and would have, had it not been for the intervening war.

Mother was a dark-haired beauty and held herself with the air of a small-town girl from Texas who had been a Zeta Tau Alpha at Duke University in North Carolina.

When Christmas came, the Texas relatives from both sides of the family descended on that small home in Prairie Village whose other inhabitants included me, my red-headed older sister Ruth, and our cocker spaniel Laddie.

Great Aunt Lucile from Austin, the unmarried former opera singer, would arrive in a mink coat and hat, a black veil across her eyes, and with a regal bearing so gracious, I realized later, she could have been entering Buckingham Palace to meet the Queen.

I was aware, even at an early age, of my parents’ attempt to avoid having both sides of the family descending on our home during the same Christmas. My mother’s parents, who I called Hoody and Tissy, did not care to compete for attention with Aunt Lucile, my father’s aunt, who had traveled the world since the 1920s. Aunt Lucile had carefully managed and grown her inherited wealth, was truly formidable, in any company, and we were all affected by her presence.

As the years passed, I realized that part of every Christmas included the push and pull within the family, old quarrels and new, always stoked anew by comparing the children, how they looked, their achievements, the colleges, the grades, the jobs.

As early as eighth grade, I began to devise ways to derail the feuding before it gained momentum — enforced caroling, reading Scripture, reciting poetry, and, when all else failed, playing show tunes and telling jokes.

Each year though, by the time the Christmas Eve darkness descended, tensions would give way to expectation, helped along by the serving of egg nog, which of course, was kept from me. By then I was too intent on the shiny, beribboned packages placed under the tree.

I would look at the tags to see how many where for me and how their size and number measured relative to those of my sister. But, the final accounting had to wait until Christmas morning when Santa’s presents would be lying unwrapped in front of the tree and the blazing fireplace.

In my memory, it seems that both Santa and my parents took great pains to make everything “even Stephen,” which is something Theresa and I have done with our own two children I realize.

Yes, I remember those nights before Christmas when I listened for reindeer hooves on the roof and the sound of Santa climbing down our chimney, perhaps delighted over the glass of milk and plate of cookies I had left for him in front of the fire.

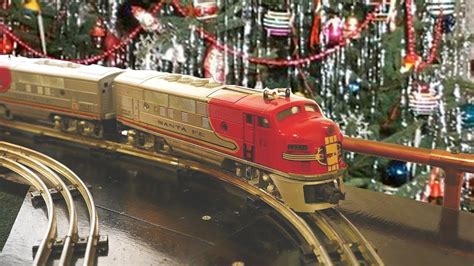

Like Ralphie in the “Christmas Story,” I always asked Santa for a BB gun, but unlike Ralphie, it never came. What did come one year, however, thrilled me like no gift I had ever received before — an electric train on a circular track controlled by a heavy transformer with a large switch on top that turned on the power and controlled the train’s speed.

My grandfather was the one who really sensed how enthralled I was with the electric train, and as soon as the gift opening was finished, he sat with me on the hardwood floor of the dining room to assemble it. The train seemed to fly around the track as I pushed the switch as far as I dared. Naturally the train lifted off the tracks a few times before I got the knack of it.

Grandfather Hoody beamed at my delight and laughter, and as I went to bed that night I felt that nothing had been missing from Christmas; the presents, the tree, the family at peace for the day, and my grandfather sharing my delight in the train set. And, oh, I can’t forget the wonderful ozone smell of that transformer when I pressed the switch as far as it would go!

The next morning came, and I rushed into the dining room to play with my train, but the transformer would not turn on, and on top of that the air had taken on the odor of something that had burned. My father, hearing my cries came in and, being an engineer, knew immediately what was wrong: “You left the transformer on all night, and it burned out.” In a moment I had lost my most precious Christmas gift, and my father had that look on his face of disappointment, the one that wrenches the heart of a young boy.

Hoody came in and tried to resuscitate the dead transformer, knowing all along it was dead and gone, but also knowing I needed someone to sit with me while I absorbed my loss. Yes, I remember that my father had warned me to turn the transformer off, but my excitement had carried me to bed, thoughtlessly turning my gain into a loss.

Sixty years later, I can remember the sting of that loss, the look on my father’s face, the gentleness of my grandfather’s gaze. It was the beginning, or should I say one of the beginnings of wisdom, a lesson in the impermanence of things. The train was taken away over night, but two memories have stayed with me from that Christmas: The parents who made Christmas day the fulfillment of a little boy’s dream and a grandfather whose love would inspire me to dream for more.