I observed in my review of Oppenheimer earlier this year that biopics were once a Hollywood staple. Now, with 2023 coming to an end, I freely admit that the “once” should be jettisoned. Oppenheimer, the soon-to-be-released Maestro (about Leonard Bernstein), and Ridley Scott’s Napoleon affirm that the genre was never dead at all; it only slept. But in the case of the new take on Bonaparte, I could wish the snooze had continued a bit longer, at least long enough for Scott to shake off the urge to make his latest film.

Biopics traditionally work on the premise that they are “based on a true story.” Such claims are often false, but, absolute fidelity to history aside, audiences have every reason to expect that the biographical subject should approximate the greatness of the real man or woman the film aims (or pretends) to realize. T. E. Lawrence was probably not like Peter O’Toole’s and David Lean’s presentation of him, but there’s no denying the stature of the man who appeared in 1962’s Lawrence of Arabia. Sure, greatness is a high bar, but it’s nothing less than fundamental to the success of the effort. We don’t want a biopic to be the diary of a nobody.

Scott’s film can’t clear that bar simply because the director chose to emphasize the commonest facet of Napoleon’s life, the love affair between the great Frenchman and his first wife Josephine. Any dewey-eyed teen can fall in love, and so can great men, but that’s not what makes them great. Perhaps Scott thought that Napoleon would live in our hearts and minds more as the lover than the warrior and emperor. Yet such a gambit all but guarantees a diminished Napoleon, anyone but the colossus we expected to find.

What we get in the colossus’s place is a love-smitten man who wants to have a son—and, oh yes, happens to be climbing to the throne of France. When Napoleon catches his first glimpse of Josephine, it’s love at first sight. It’s sex at first opportunity too. In short order, he herds Josephine upstairs, lifts her dress, and does what comes naturally. These catch-as-catch-can sex scenes punctuate the action like semicolons in a freshman essay, which is bad enough, but, worse still, they can be outrageously ridiculous. Take, for example, the scene where the amorous pair lunch together in grand, aristocratic style. Suddenly, Boney decides the time is right and crawls the full length of the table (a good fifty feet, I’ll bet) to Josie whom he pulls to the floor for postprandial coitus.

Such moments, absurd as they are distracting, trivialize the man. Is he really in love, randy as a goat, or just hellbent on begetting an heir? The answer to that question is a toss of the coin and, except that we’re at least supposed to be watching Napoleon, largely irrelevant. Nonetheless, with the bit clenched between his teeth, Scott won’t let the matter rest, so we must follow not only the great man’s life but Josephine’s also, right up to her death from an unnamed respiratory ailment. Happily, Scott left it to us to speculate whether it was an early form of Covid.

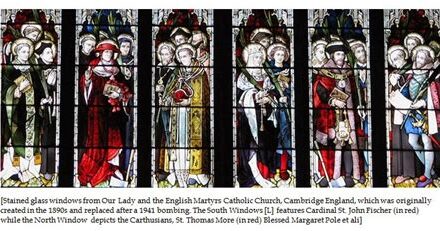

Above all, Napoleon was a military genius, and the eponymous movie gives an adequate but sometimes unhistorical view of the man at war. The attack on Toulon where he surprised a British garrison and turned its cannons on the blockading squadron has its exciting moments, even though Napoleon, still a captain of artillery, did not have his horse shot from under him. His key battle at Austerlitz in 1805 gave him his greatest victory. The snow on the field, described by at least one historian as a light dusting, is overdone in the movie. That’s a minor quibble. But Napoleon did not command the heights, as Scott’s film shows, but rather chose the lower ground to give his enemy, an Austrian-Russian alliance, a false sense of advantage; when he attacked, he audaciously charged uphill, a gamble that paid in a rout of the opposing force. Like Nelson’s daring at Copenhagen, that’s miliary genius, but you’ll know nothing of it in Scott’s telling. Furthermore, the cannonade of the fleeing Austrians and Russians on the frozen pond is of doubtful historicity.

The famous 1812 Russian debacle in which Napoleon lost over half-a-million men is all too sketchy to convey the degree to which it ruined him and imperial France. Even the horrendous carnage at Borodino gets short shrift. Better to watch a good version of War and Peace. (I suggest the 1972 BBC miniseries with Anthony Hopkins—yes, better than the acclaimed Soviet production.)

As for Waterloo, Scott fares better. For one, the scale of the battle is approximated. But pivotal moments, the fights at Hougoumont and Seinte Haye, are ignored. Worse still, Ney’s fatal charge on the English squares gets misrepresented. The French cavalry general leading 4,500 horsemen believed the English were in full retreat; they weren’t, and when it was too late to withdraw, Ney’s men found themselves in a deadly fusillade, a turning point (but by no means the end) of the single bloodiest day in modern European warfare up to that time. To Scott, the decision to charge falls chiefly on Napoleon’s shoulders; regardless of what history suggests, it appears on film that Ney sees the squares clearly from the start. Does Napoleon? Is that miliary genius?

Most of the acting throughout has real merit. Vanessa Kirby’s Josephine is impressive although I could have done without her barely suppressed mirth at the divorce ceremony. Ben Miles as Caulaincourt provides a steady presence, as does Paul Rhys as Talleyrand. With respect to the latter, Scott missed a chance for Napoleon to call the great chameleon, courtier, and diplomat a “piece of dung in a silk stocking.” Then again, he also failed to work in the emperor’s quips about the pope (“How many divisions?”) and the English (“a nation of shopkeepers”). Rupert Everett’s Wellington is perhaps twenty years too old, but he has the Duke’s features, as well as his calm in the thick of battle.

The greatest flaw in casting, however, is Joaquin Phoenix as Napoleon. A good, sometimes very good actor in the right role, he is for much of the “bio” too old and generally too deadpan to be compelling. Plainly, the magnetism that the great general and statesman doubtless possessed eludes Phoenix. Face facts: if the raison d’etre of a biopic, namely its subject, lies beyond the grasp of the main actor, the result cannot be successful.

It is to Scott’s credit that I was not bored watching Napoleon; the story, with all its glaring flaws and ludicrous fabrications, unfolds at a steady pace—no small feat for a film that purports to cover thirty-two years. Still, for Napoleon at war, I’ll opt for Waterloo (1970), and if I must watch Napoleon in Love, I’ll take Marlon Brando and Jean Simmons in Désirée (1954). At least, Brando’s Napoleon refrains from dragging Josephine or Désirée under the dinner table.