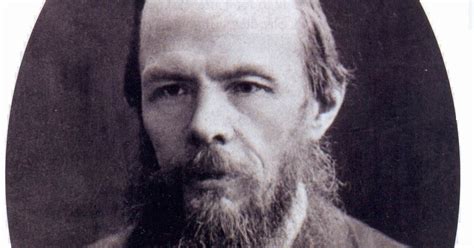

Those who have been blessed to read Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, possibly the greatest novel ever written, will recall the central place of “active love” in the story. Active love is an easy thing to define—or easy enough—as the practical application of the highest of the theological virtues. In Dostoevsky, it is the essence of Christian living, seen memorably in the life of Father Zosima, the Russian monk who acts not only as Alyosha Karamazov’s mentor but, more importantly, as Dostoevsky himself insisted, as the living refutation of Ivan Karamazov’s imaginative creation, the infamous Grand Inquisitor.

Any reader of the book will note in the statement that concludes the previous paragraph an implicit criticism or, colloquially speaking, a put-down of Ivan. His ideal, if we may call it that, was only in his head; Alyosha’s Zosima was a living breathing man whom the rebellious Ivan had in fact met. And, no doubt, that’s exactly what Dostoevsky wanted us to see. A harsh opponent of Western rationalist schemes, of systems spun from the heads of intellectuals, which had nothing to do with man as he actually was, the great Russian author spent most of his mature years as novelist and journalist fighting those who sought to impose rationalist ideas on his country.

Active love, visible in the selfless giving to another as an imitation of Christ would, Dostoevsky was sure, ultimately triumph over the tyranny of the godless mind.

An invisible skeptic (and Dostoevsky created one or two) might object, “Well, haven’t you committed a grave error in logic, even an existential slip?” I plead guilty. Of course, there is always an internal flaw in the claim I’ve just made, and it’s simply this: Alyosha Karamazov and Father Zosima were no more real than Ivan’s Grand Inquisitor. So how active can active love be if it’s stuck in the pages of a book? How now? How then? How anytime?

Happily, Dostoevsky’s life provided him with examples of active love so compelling that he and we too would be fools to ignore them; moreover, some of these instances occurred very early in his life, years before he became the great author we all know. To me, a certain event stands out.

Anybody who has read even a little of Dostoevsky’s biography will know that on April 23, 1849, St. George’s Day, at four o’clock in the morning, he was arrested for illegal political activity, chiefly being part of a radical group that obtained a printing press and planned to distribute leaflets calling for the abolition of serfdom. The propaganda might have gone as far as advocating a serf uprising, but it’s hard to say because the leaflets never saw the light of day.

After months in the Peter and Paul Fortress Prison in St. Petersburg, Dostoevsky suffered the horror of a mock execution before a firing squad, after which he was packed off to Siberia for four years of hard labor followed by indefinite service in the army.

It was in Siberia before he reached the camp that Dostoevsky met some living, breathing practitioners of active love. These were women, mostly of noble birth and in some cases of great refinement and education. The wives of the political exiles known as the Decembrists, they had followed their husbands to Siberia and, perhaps out of necessity but assuredly from love, had resided there for nearly twenty-five years when Dostoevsky met them.

In his great five-volume literary biography of Dostoevsky, Joseph Frank quotes the Russian author about these women. He called them “sublime sufferers.” If we think of the “sublime” in its technical sense as a thing or deed that rises above beauty to indescribable heights, the word is exactly right. Dostoevsky later wrote:

“When we sat in prison awaiting our further fate . . . the wives of the Decembrists pleaded with the overseer of the prison and arranged a meeting with us in his quarters. We saw these sublime sufferers, who had voluntarily followed their husbands to Siberia. They gave up everything, position, wealth, family ties, sacrificed everything for the highest moral duty, a duty which nothing could impose on them except themselves. Completely innocent, during twenty-five years they bore everything to which their husbands had been condemned . . . They blessed us as we entered on a new life, made the sign of the cross, and gave us a New Testament—the only book allowed in prison . . . I read it sometimes, and read it to others. With it, I taught one convict to read.”

Frank adds that in the binding of each New Testament the prisoners found ten rubles.

An empty ritual? Hardly. Of Mme. Fonvizina, one of these sublime women, it was observed that her religion was much more than an adherence to outward forms or even occasional generosity. She “lived an inner, religious life in the full sense of the word,” reading the Bible till she knew it “almost by heart” and delving in to a variety of religious authors—Orthodox, Roman, and Protestant. If a book could nourish the Christian soul, it was worthy of her full attention. The other women may not have been quite as remarkable, but their actions were as selfless.

And their deeds did not end with that. When the prisoners were transferred farther into Siberia, Mme. Fonvizina and Marie Frantseva arranged to meet Dostoevsky and fellow political prisoner Sergey Durov in “frightful cold” to bid them farewell and give them a letter to Lieutenant-Colonel Pushkin to treat the two men as civilly as possible.

Many of the women in Dostoevsky’s novels lack the social status of these extraordinary ladies, but they share with them the determination to practice active love, a determination that becomes a spiritual habit and, without exaggeration, a joy to themselves and others. The pitiful Liza in Notes From Underground, Sonya (especially in the Epilogue) in Crime and Punishment, and the repentant Grushenka in The Brothers Karamazov aren’t the product of an overly fertile imagination. They’re based on real women who were so selfless in their love that, except for the historical record, they might seem too good to be true.

The instances of active love in Dostoevsky are, it’s fair to say, the hallmark of his art. When Alyosha kisses the earth in The Brothers Karamazov, he does more than humble himself. He proclaims that active love exceeds the merely ideal; it is both real and practical. And I hope I can say it without sounding redundant, he then practices it. Dostoevsky could paint such a career in absolute confidence because he’d seen it in flesh and blood at a time when he had perhaps his greatest need of it.

Too good to be true? Thank God it’s not.