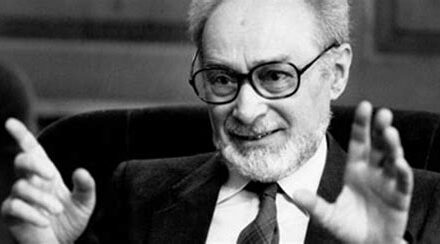

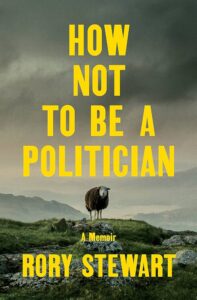

Rory Stewart stands out as one of the most interesting authors of recent times, in part due to the different paths he has chosen. Born in Hong Kong, raised in Malaya (where his Scottish father was in the foreign service), educated at Eton and Balliol College, Oxford, he served a tour of duty in the British army before becoming a diplomat in Indonesia and eventually Iraq. In 2000 to 2002, he hiked part of southern Asia on foot, notably across Afghanistan, memorably recounted in his book The Places In Between. Later, he walked the route of Hadrian’s Wall, a story told in The Marches, ran an NGO in Afghanistan to aid the district around Turquoise Mountain, and accepted a professorship, at Harvard—all before he turned thirty-eight. And then he ran for Parliament.

This last leg of his career provides the subject of his new book How Not to Be a Politician, and although it was published in the UK as Politics on the Edge, the American title seems apropos. Indeed, as Stewart’s narrative unfolds, a reader may wonder, first, why he decided to run in the first place, and second, whether he is temperamentally suited for the job. As for the first question, Stewart entered Parliament, in the words of his Canadian friend Michael Ignatieff, “to make a difference.” The matter of his temperament remains a more difficult business and, I suppose, depends upon how cynical one is about politics. I’d have to say the life suited him well enough since he rose in government, slowly at first under David Cameron and more rapidly under Theresa May, dealing with a variety of posts with a determination and skill few could have mustered. But did he have the drive to simply get on with the program?

After walking much of Cumbria in his first campaign, meeting voters and staking out a few positions of local interest, Stewart improbably won his first election in 2010 and headed for Westminster as a Conservative. As commonly happens, he spent time as a backbencher, but quicker than many, and in time managed to gain the chairmanship of the Defense Select Committee. When, after five years, Cameron summoned him to Number 10 to offer him the post as under-secretary in the Department of Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), a “most junior position in perhaps the most junior department in government,” he accepted, and, typical of the man, threw himself into the task wholeheartedly

But in this appointment, the problems with the British system begin to emerge. Given his background, Stewart expected a post in the Ministry of Culture or in the Scottish Office. As enthusiastically and even successfully as he managed his duties in DEFRA, his apparent strengths hardly suited him for that department. Yet there he was. And as soon as he began to feel he was making a difference, the new PM Theresa May appointed him Minister of State in the Department for International Development (DfID).

Again, he acquitted himself well, rushing between his office and Parliament for key votes, but frequently battling entrenched civil servants who regarded the operations of the department their sole province. Even so, his experience in the Middle East served him at least to some degree. When some officials presented him with a plan for funding municipal councils in Syria, he stood firmly against the move because he knew the “enclaves” were “controlled by jihadi factions.” The dark comedy that followed might have been from an episode of Yes, Minister. Stewart’s veto of the program itself got vetoed. Who did the vetoing? Nobody knew, and Stewart went from group to group to make his case that the funding was ridiculous and harmful. Despite some of them insisting that the money indeed must not go to the Syrians, it kept flowing. Every document he saw pertaining to the policy strangely lacked any reference to Stewart’s objections. After two months, a Middle East director brought proof that the municipalities were siphoning off the “aid” to the benefit of al-Qaeda and instructed Stewart “to terminate the funding.” As Stewart ruefully notes, “There was no acknowledgement of my campaign, but the funding somehow ceased.”

Stewart’s being shuffled and re-shuffled doesn’t stop there. Briefly in a position where he has real knowledge, Foreign Minister Boris Johnson decides, as if on a whim, to send him to Africa. Once he feels comfortable there, he’s shifted to Justice to oversee prisons. Working tirelessly to remedy horrific conditions in British jails, he finds himself unexpectedly back in DfID as its Secretary of State. After May’s announced resignation, as if to take the bull by the horns, Stewart puts his name forward for PM but fails in his bid, perhaps the most frustrating reading in the book.

Amid the tumult of such unpredictable yet predictable change stands the Remain/Leave vote, the yay or nay on “Brexit.” Stewart, a “One Nation” Conservative (derisively called a “wet”), chooses the Remain side. Yet he honors the result of the referendum while insisting that a “no-deal” Brexit will be disastrous to the nation’s farmers and businesses. Although his pro-Remain justification seems rather thin, I can understand why he opposed “no-deal,” and I suspect time has proven him right. On other issues, he’s sometimes miles away from a traditionalist conservative stance, supporting radical environmental policy (“climate cataclysm”), immigration, the BBC, and Cameron’s reform permitting gay “marriage.” On the other hand, he maintains an essentially Burkean view of localism, “prudence at home,” and “restraint abroad.”

That said, I find his “vision for Britain,” expressed during a run in Hyde Park, consisting of some middle-aged men, a few Saudis “in ironed jeans,” various runners, “and women in saris” that he passes, a far cry from Edmund Burke.

How Not to Be a Politician presents a stage of characters, many of whom are well known to Americans. Cameron and May, whom Stewart respects, make their inevitable appearances. So do Liz Truss and, by name only, Jacob Rees-Mogg, both of whom he despises although for very different reasons. He reserves his full contempt for Boris Johnson, a man he sees as excessively mercurial, untrustworthy, and wholly unfit for the office of PM or, I suspect, for any office. That assessment may give Americans reason enough to read Stewart’s book, provided, of course, they can find a figure or figures—perhaps too many—on our country’s stage that resemble Boris. Otherwise, read it to find out why we don’t want a parliamentary system that Stewart all but acknowledges is broken.