Madeleine L’Engle was a remarkable woman. To this writer’s thinking, she was the last in a chain of Anglican or Anglo-Catholic writers who used the genres of Fantasy, Horror, Science Fiction, Mystery – or sometimes a mixture of two or more – to express their views of objective reality while spinning a tale.

Her predecessors in this dynasty include C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, Dorothy Sayers, G.K. Chesterton, M. R. James, Ralph Adams Cram, and Arthur Machen. What an anonymous Wikipedia writer declared of Miss L’Engle is without doubt also true of her predecessors: “A theme, often implied and occasionally explicit, in L’Engle’s works is that the phenomena that people call religion, science, and magic are simply different aspects of a single seamless reality.”

Going back to the Medieval Scholastics and beyond, this view is what gives these authors’ works their power. It is also what led to occasional accusations against Miss L’Engle of New Agery – with the divide seeming to run along the liturgical fault line.

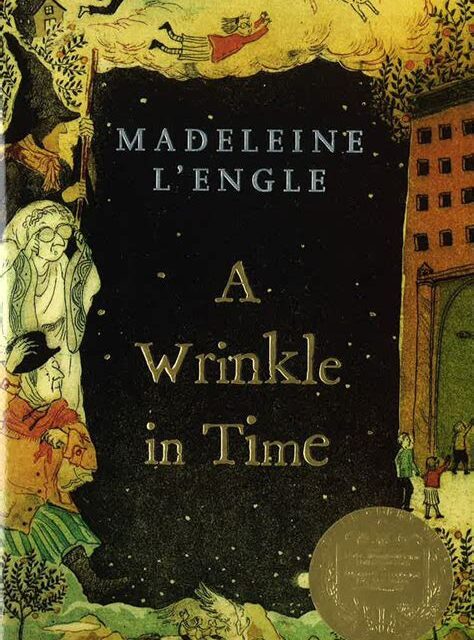

Now, I would not want to say that Miss L’Engle’s writing was flawless; her theology as expressed in her non-fiction suffered from the general doctrinal collapse of Anglicanism in the 20th century, and she was certainly a Christian Universalist. But her fiction was filled with scriptural and religious references, and in A Wrinkle in Time Christ is explicitly revealed as the chief of the “fighters of the light” – unlike the others, His identity is revealed through an apropos quote from the Gospel of St. John.

This book offers us the Murry family, whose brilliant scientist father Alexander has vanished a year ago in a government facility, equally brilliant wife Katherine who is struggling to keep things together, brilliant student but socially awkward 13-year old daughter Meg, twins Denis and Sandy, and five year old Charles Wallace – who is abnormally brilliant, and telepathic as well. Meg, Charles Wallace, and her classmate Calvin O’Keefe are visited by three apparent witches, who reveal that Alexander vanished through a “tesseract,” and is being held prisoner by a monstrous entity on Planet Camazotz, called IT.

IT’s hapless subjects are forced to live in endless conformity to their master’s will and rhythm (the latter quite literally). Eventually, the three witches are revealed to be planetary angels (remember Plato and St. Thomas Aquinas), whose worlds did not survive the struggle with the Dark, of which IT is a leading avatar. After several visits to other worlds as a sort of training exercise, the three children are sent to find and free their father.

As with Lord of the Rings, one approaches a much-loved novel-turned-to-screen with trepidation and should bear in mind that what is seen on the screen shall never be the movie in one’s head. One makes allowances – and also remembers that plot intricacies often do not translate well into cinema. But there are elements that are central to a writer’s vision – removing the element of Providence from LOTR would have sunk that film – and Jackson, regardless of his personal beliefs, wisely did not do it. In 2003, Disney ordered a Canadian made-for-TV movie of A Wrinkle in Time. Most of the religious element was excised, and Miss L’Engle cheerily said: “I have glimpsed it… I expected it to be bad, and it is.” Watching it myself when it appeared, I was severely disappointed.

Well, 15 years have passed; society is more secular – one might even say stupider – than it was then. Disney announced it was doing a big screen version. Jennifer Lee would write it, and all the Christian themes were to be explicitly scrapped. Asked Why Miss Lee’s response was:

“What I looked at, one of the reasons Madeleine L’Engle – as I’ve been told; I never got to meet her – but one of the reasons it had that strong Christian element to it wasn’t just because she was Christian, but because she was frustrated with things that needed to be said to her in the world and she wasn’t finding a way to say it and she wanted to stay true to her faith. And I respect that and I understand those feelings of things you want to say in the world that need to be said that are out there. In a good way, I think there are a lot of elements of what she wrote that we have progressed as a society and we can move onto the other elements. In a sad way, some of the other elements are more important right now and bigger – sort of this fight of light against darkness. It’s a universal thing and timeless and seems to be a battle that has to keep being had.” (Emphasis added)

Having seen the picture now, I can say that the same sort of clarity Miss Lee demonstrates in interviews is apparent in the film. Visually beautiful, with a fine cast that struggles manfully with the material, it is a great train-wreck of a film, pop psychology replacing Miss L’Engle’s ideas entirely. Oprah Winfrey, as the enormous Mrs. Which, seems to be already campaigning for the 2020 election. There are long dragging stretches, and the evil of Camazotz’s conformity is reduced to simply being a 1964-era suburb. Directed by Ava DuVernay, much is made of this being the first multi-million dollar film directed by a black woman. That is nice but cannot recoup everything else about it. Nice CGI, though.

When I got home, as an experiment, I watched the 2003 TV movie. In the light of what I had just seen, it was SO much better, SO much truer to the book – there were even mentions of grace and St. Paul – and the liberation of Camazotz is actually touching. So here is my advice, for what it’s worth. If you have not read the book, instead of seeing the current mishmash in the theatre, go home and plunk down $1.99 to Amazon, and watch the TV movie. THEN read the book, and you’ll be amazed at how really good it is.

I just had the same experience. The 2018 movie had a wonderful cast; Storm Reid was good as Meg. But, in spite of the cast and the special effects, it left me completely unmoved. The older movie was also well cast (though both films got Mrs. Which very wrong), much closer to the books, and surprisingly powerful and touching in its good moments. It also flowed better than the newer movie and made more sense.