50th anniversary Edition

Published by Harcourt Brace and Company (September 4, 1998)

467 pages

Working on my recent review of Whittaker Chambers’ autobiography Witness made me think of another classic story of conversion from the mid-20th century that continues to attract readers and change lives. Both stories should interest serious Christians of any tradition, but Merton’s should particularly interest Catholics and all who revere the contemplative life.

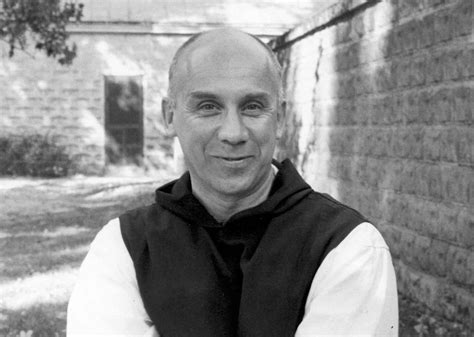

Merton, who was born a century ago this year, is best known for his 1948 autobiography The Seven Storey Mountain, a book that sent scores of World War II veterans, students, and even teenagers flocking to monasteries across the U.S. for retreats and in some cases in pursuit of a vocation.

Merton was most certainly a conflicted man throughout his life, but at the same time he became one of the greatest spiritual writers of the latter part of the 20th century. By the time of his death overseas in Thailand at the age of 53 in 1968, he had written more than 70 books on spirituality, some of the best known being The Seeds of Contemplation (1949) and Raids on the Unspeakable (1966).

Born in France in 1915, Merton was accustomed to being on the move, spending extended periods in the U.S., France, and England, as his father was a well-known artist in London and elsewhere.

Merton’s first real taste of Catholicism came while he was visiting Rome and Florence in his late teens. The attraction he felt, while its immediate effects soon dissipated, had a lasting effect. However, during his time at Cambridge he started drinking heavily, running through money, and engaging in sex. The portion of the autobiography where he recounts this was somewhat censored by the monastery so as not to offend or scandalize the readers of that time, when Rev. Fulton Sheen’s “Life is Worth Living” was ruling the early TV era.

Moving back to the United States in 1935, Merton enrolled as a sophomore at Columbia University, after a year at Clare College in the UK, where he made lifelong friends, several of whom were Catholics. Browsing in the Columbia library, he encountered a book that opened his mind to Catholicism more fully: Etienne Gilson’s The Spirit of Medieval Philosophy. Here he found an explanation of God that started to answer both both logical and pragmatic questions about faith.

He also read the poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins, a late 19th century Jesuit who had been received into the Church by Cardinal Newman, and began to seriously consider Catholicism and the priesthood. In the end he sought instruction from a priest at Corpus Christi Church, near the Columbia campus. On November 16, 1938, Merton himself was received into the Catholic Church. The next year he was confirmed at the same parish taking the name, “James.”

During the next several years he searched for his vocation, finally arriving at the Abbey of Gethsemane, a Trappist monastery, on December 10, 1941. After three days there, he sought acceptance into the order and was received as a postulant on the first Sunday in Lent, 1942.

The next stage of his life arrived after receiving permission from his superiors to publish The Seven Storey Mountain, which became an enormous success, becoming one of the best-selling non-fiction books of 1949. By 1984, the paperback edition sold over three million copies, while the hardback edition sold over 600,000.

That book covers only the first few years of his monastic career, but from this point on his superiors permitted him to write many more books of spirituality, many of which were controversial due to his advocacy of social justice and his opposition to war in general and the Vietnam War in particular.

Interest in Merton and his work has never waned. There have been a number of biographies of Merton, and his major books have stayed in print and continue to be read. Towards the end of his life he was granted permission to live in a hermitage on the monastery grounds. There he continued to correspond with well-known figures throughout the world, and at the end of his life even visited Asia to dialogue with Buddhist monks in pursuit of common ground.

He died on December 10, 1968, there in Thailand, when a fan fell into his bathtub and electrocuted him. Despite his restlessness, temptations, to the end he remained a committed Catholic. Indeed, in his last letter to his fellow monks he wrote, “In my contacts with these new friends, I feel consolation in my own faith in Christ and in His indwelling presence.”

One day a great movie will be made of Merton’s life. Merton was no saint, but in spite of all his difficulties he persevered in the faith that had rescued him from the emptiness of 20th century secularism. And in doing so, offered through his writing a compelling portrayal of a restless man settling for nothing less than God.

great article

Now reading Seeds of Contemplation. Wonderful!

Will check it out after this book!

Fine writer

May I suggest a read of; Beneath the Mask of Holiness by Mark Shaw, uncensored by the way! It presents not only the spiritual but the human side of Merton, the whole man. This is representative of all of us. This is a book that Merton himself would have approved of, as demonstrated by his journals.

I am not sure that Merton remained Catholic or even Christian at the very end. A few days before he died, Merton was filmed in Thailand in a documentary about him. Even though I saw this documentary 30 years ago, I still distinctly recall something that Merton said therein that struck me as extremely odd at the time, and remains with me to this day. He had just visited one of the great Buddhist shrines of Thailand, and in his comment to the interviewer, he stated that one of the most mystical experiences of his life was the moment he walked into the shrine and beheld the great statue of Buddha. It seems difficult to reconcile his impression of the moment with the idea that he was at that time of his life a devout Christian.

We may well have been a saint. One thing for sure he brought many people to the monastic life, my self being one. Although I never joined the order his presence led me to a newer closeness to God through spiritual reading. Merton was big on spiritual reading and contemplation.

I believe he was murdered because of his outspoken opposition to the war .

Just as I believe Martin was murdered for the same reason.

For those who have study mysticism and are contemplatives,mediators ,Merton statement would not come as a surprise.

Both figures Christ consciousness and Buddha consciousness point to our ineffable connection to the divine.

The review by Fr. McCloskey is superficial and sloppy without even an attempt to verify basic facts about Merton. The conclusion that “Merton was no saint” is laughably inadequate.

The Wikipedia entry for “Thomas Merton” states:

“In April 1966, Merton underwent a surgical procedure to treat debilitating back pain. While recuperating in a Louisville hospital, he fell in love with Margie Smith,[27] a student nurse assigned to his care whom he referred to in his personal diary as “M.” He wrote poems to her and reflected on the relationship in “A Midsummer Diary for M.” Merton struggled to maintain his vows while being deeply in love. He never consummated the relationship, which had a sexual component.[note 1]”

Note 1 states:

“This issue is discussed in detail in Shaw, Mark (2009). Beneath The Mask of Holiness. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-230-61653-4. In Learning to Love, Merton’s diary entries discuss his various meetings with Smith, and in several cases he expressly denies sexual consummation, e.g. p. 52. However, on Saturday, June 11, 1966, Merton arranged to ‘borrow’ the Louisville office of his psychologist, Dr. James Wygal, to get together with Smith, see p. 81. The diary entry for that day notes that they had a bottle of champagne. A parenthetical with dots at that point in the narrative indicates that further details regarding this meeting were not published in Learning to Love. In the June 14 entry, Merton notes that he had found out the night before that a brother at the abbey had overheard one of his phone conversations with Smith and had reported it to Dom James, Abbot of Gethsemani. Merton wondered in his diary which phone conversation had been monitored, saying that a conversation he had on Sunday morning, i.e., the morning following the meeting with Smith at Wygal’s office, would be “the worst!!”, see p. 82. The June 14 diary entry also describes Merton’s discussions with Abbot James in this regard, and Merton’s intent to follow the Abbot’s instruction to end his romantic relationship with M. Roughly a month later, in his entry for July 12, 1966, Merton says regarding Smith, “Yet there is no question I love her deeply … I keep remembering her body, her nakedness, the day at Wygal’s, and it haunts me … I could have been enslaved to the need for her body after all. It is a good thing I called it off [i.e., a proposed visit by Smith to Gethsemani to speak with Merton there following their break-up, which Merton called off].” See p. 94. Learning to Love reveals that Merton remained in contact with Marge after his July 12, 1966 entry (p.94) and after he recommitted himself to his vows (p. 110). He saw her again on July 16, 1966, and wrote: “She says she thinks of me all the time (as I do of her) and her only fear is that being apart and not having news of each other, we may gradually cease to believe that we are loved, that the other’s love for us goes on and is real. As I kissed her she kept saying, ‘I am happy, I am at peace now.’ And so was I” (p. 97). Despite good intentions, he continued to contact her by phone when he left the monastery grounds. For example, he wrote on January 18, 1967 that “last week” he and two friends “drank some beer under the loblollies at the lake–should not have gone to Bardstown and Willett’s in the evening. Conscience stricken for this the next day. Called M. from filling station outside Bardstown. Both glad” (p. 186).’

This is interesting. I have about 5 more pages left in Seven Story Mountain and will finish it this afternoon. I live in Louisville, about 45 miles from Gethsemane, where I bought the book.

What do you think of spiritual insights Louie?

I agree to an extent with Mr. Cross. In reading the later letters of Merton, along with some of his other works relative to his visits and reaction to his trip to India, I feel he was at least in danger of straying away from the Faith. So although his earlier works and his journey to the Faith are to be highly respected, it appears there was more going on than was immediately apparent towards the end of his life. His death at a relatively early age due an unsafe electrical cord to a fan in his room in Thailand (I think Thailand) makes it impossible to determine what direction he ultimately would have traveled.