Anti-Catholicism arrived on the shores of America with the first English settlers. In the first sentence of his history Of Plymouth Plantation (Modern Library college edition, 1981), William Bradford, the second governor of the Colony of New Plymouth, or The Plymouth Plantation, speaks of the Satanic opposition the “godly and judicious” of England have endured since “the first breaking out of the light of the gospel” after the Lord had lifted from their nation “the gross darkness of popery which had covered and overspread the Christian world.”

John Winthrop preached that the Puritans would establish “a city upon a hill,” a light to the world that would be “a model of Christian charity.” But for all the good they did and meant to do, the Puritans had no charity for Catholics, excluded Catholics from their city, and became a byword for anti-Catholicism and religious intolerance.

In The New Anti-Catholicism: The Last Acceptable Prejudice, Philip Jenkins, a professor of history and religious studies, a former Catholic turned Episcopalian, quotes three prominent writers and historians, who have called America’s anti-Catholicism the nation’s “ugly secret,” “deepest bias,” and “most luxuriant, tenacious tradition of paranoiac agitation.”

Anti-Catholicism has remained the nation’s ugly bias and tenacious tradition throughout its history, from the first days of Plymouth Colony to the tumultuous history of religious tolerance in Maryland and Pennsylvania, the fight of the colonists for liberty from England in the American Revolution, up to the Obama administration’s efforts to force Catholics to participate in the funding of contraception and abortion under the guise of national health care, and into the present day through the efforts of leftist politicians and political activists intent on creating a collectivist paradise tolerant, if at all, of only a tinsel Christianity.

Yet despite bigotry, persecution, and subtle and even overt oppression, all too often with the support of lukewarm and misguided Catholics (including Jesuits), Catholicism has grown from a seed planted in the colonies to a tree with deep roots that span the nation.

Fr. Charles Connor, a professor of theology and Church history at Mount St. Mary’s Seminary in Maryland, tells the story of what early American Catholics endured, and the contributions they made in the forging of our nation, in Pioneer Priests and Makeshift Altars: A History of Catholicism in the Thirteen Colonies (EWTN Publishing).

Rich in detail, Pioneer Priests and Makeshift Altars is framed by the story of two revolutions: the European revolt against the Catholic Church, in particular, that of the English, and the revolt of the American colonies against England.

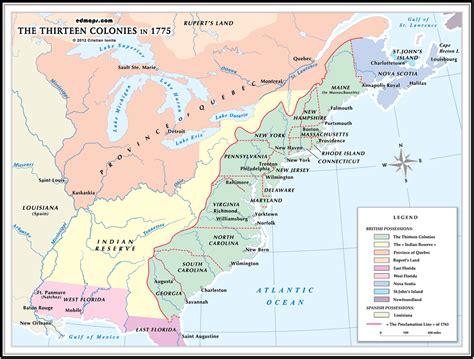

Attitudes formed through the revolt against the Catholic Church were the root of the bias of English and Dutch settlers toward Catholics in America, a bias that held steady up to and after the American Revolution. Of the thirteen colonies, Connor writes, only four wrote constitutions that gave Catholics the freedom to practice their faith after the war: Maryland, Virginia, Delaware, and Pennsylvania.

While a substantial part of Connor’s book concerns the history of Catholics in Maryland, the book also covers the experience of Catholics in Pennsylvania, Delaware, New York, New Jersey, and New England.

Connor’s focus on Maryland is essential. The history of Catholicism in the English colonies begins with Maryland when Cecil Calvert carried out the settling of the territory his family had been granted after his father’s death with the aim of creating a refuge for Catholics. “Maryland was to be a colony conspicuous for religious tolerance,” Connor writes, adding that this was “at least for a time.”

As monarchs and leaders changed in England, the colonists in America suffered from their changing attitudes toward Catholics. The Calverts eventually lost their family’s charter and in 1704 Catholics were forbidden to celebrate or participate in public Mass in Maryland. By 1705 Catholics had lost their rights throughout the English colonies, including, despite William Penn’s opposition, Pennsylvania.

While it is an excellent synthesis and overview of the Catholic experience in America, Pioneer Priests and Makeshift Altars is also the story of those who helped make the United States the standard bearer for religious liberty for the world. Throughout the book, Connor skillfully interweaves the stories of the renowned, little known, and unknown men and woman who played great and small parts in ensuring religious liberty in the colonial and formative years of the nascent United States. Among those Connor writes of are the Calvert and Carroll families; Jesuits Andrew White, John Altham, and Thomas Gervase, who were among the settlers of Maryland; Marylander Ann Matthews, who became the first superior of the first women’s monastery in the colonies; and Stephen Moylan of Pennsylvania, who became Washington’s aide-de-camp and later was named Quartermaster General of the Army and a Colonel.

The history of early Catholicism in America also is the history of the great sacrifice made by Jesuits as missionaries. They were among the first English settlers in Maryland in March of 1634 and were with the French in New York in the 1640s. They were present across the continent and in addition to the colonies could be found in Acadia, Ontario, Wisconsin, and the Mississippi Valley.

The Jesuits traveled long distances to bring the faith to Catholic settlers, and they brought the faith to the Iroquois Nations. They said Mass in private homes, founded schools and served as teachers, died as martyrs (a total of eight by 1649), helped in establishing the first women’s monastery in the colonies (Discalced Carmelites), and formed and educated the new nation’s first bishop, John Carroll, who was selected and named bishop in 1789 and consecrated in 1790.

Pioneer Priests and Makeshift Altars is a great reminder of the price paid by those who refused to give up their Catholic faith and those who joined them in the fight for religious liberty, a liberty we have inherited from them and, if we are to honor them, a liberty we are obligated to defend at all costs.

Christ is Born!

Does this book mention anything about the Eastern Catholic Churches?

In the Infant King,

Margaret

Not that I recall. The Eastern presence, for the most part, is later. Russians were in Alaska in 1740, but Alaska isn’t part of the book’s focus. Some Greeks arrived in Florida about thirty years after that, also not part of the focus, and began to become established in New York in the mid 1800s. The Maronites arrived in 1854. Eastern Catholics from the Russian Empire began arriving in the late 1800s. Most of this information can be found through Wikipedia.

Thank you, Father Deacon!