Over thirty years ago, I left the Southern Baptists and was confirmed as a Roman Catholic. There were many reasons for my conversion but among the most important was their suspicion and fear of culture. I was taught God spoke only through the “Bible,” properly interpreted of course, and Catholics believed in “idols” beginning with the Virgin Mary.

The Catholic Church that I discovered didn’t believe in idols but embraced God’s presence in culture and history, beginning with the saints and including the arts, sciences, humanities, philosophy, and even politics. His presence was encountered throughout creation and among the descendants of Adam and Eve, in all that they did, thought, made, imagined, dreamed, and what they created made the limiting of Christian wisdom to Scripture both unnecessary and “downright un-Biblical.”

While Scripture and tradition remained normative among Catholics, both the knowledge and experience of God were viewed as ubiquitous, literally everywhere.

Thus, when I encounter the same a negative attitude towards culture among fellow Catholics I get cranky. Over the past thirty years, I have watched as good people bailed out of the “culture wars” either because the good guys were losing or it just no longer appealed to them, while others have decided to “say goodbye” to the division between “left and right.” (And I have lost count of the number of times in the past 30 years this has been announced.)

The so-called “Benedict Option” takes another approach to erasing the tension between faith and culture — the retreat to the safe environs of a home and community where the incoming cultural “stimuli” can be intercepted and repelled.

That these sentiments emerge among Catholics from to time to time testifies to the Puritan-Protestant roots of our nation’s culture. As Alexis de Tocqueville wrote after his American visit in the 1930s, “methinks I see the destiny of America embodied in the first Puritan who landed on those shores, just as the human race was represented by the first man” (Democracy in America, Ch. 17.1). As a result of this pervasive influence, Catholics in America have been attacked head-on throughout our history, think of the Blaine Amendment (1875) and Prohibition (1917). But instead of Catholics reaffirming their unique heritage, and in spite of the exclusion, persecution, and prejudice, they self-appropriated much of the Protestant criticism which led them to find a safe refuge in self-doubt and conformity.

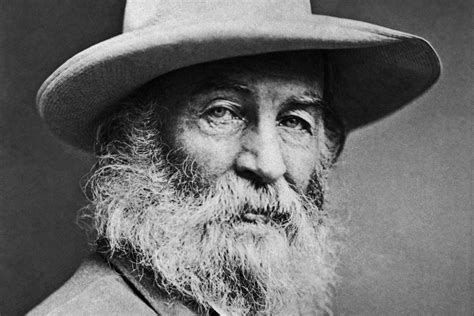

Let me propose another option, one both more Catholic as well as being American in the best sense: The Whitman Option, named for one of the greatest of our native poets, Walt Whitman (1817-1889). More than reprinting his words from “Leaves of Grass” (1855-1892), I’m posting his words set to music by the composer Ralph Vaughn Williams, an Englishman, who like many artists of his generation, were inspired by Whitman’s unabashed poeticizing in free verse about the body, soul, nature, and God. In A Sea Symphony (1910), Vaughn Williams found the music to match the irresistible desire, unforeseen exultation, and the expanding vision of a soul seeking God.

The Whitman Option goes in the opposite directions from those who seek either refuge from, or a faux reconciliation of, the tensions between faith and culture: a radical openness to seeking and embracing all that is good, beautiful, and true in our world. Rather than a theological argument, two lines of Whitman will guide us: “Bathe me O God in thee” and “Are they not all seas of God,” lines which combine the desire for God with His ubiquitous presence.

In the final section of the “A Sea Symphony,” called “The Explorers,” the two solo voices announce their intention to “launch out on the trackless seas . . . singing our song of God.”

O we can wait no longer,

We too take ship O soul,

Joyous we too launch out on trackless seas,

Fearless for unknown shores on waves of ecstasy to sail,

Amid the wafting winds, (thou pressing me to thee, I thee to me, O soul,)

Caroling free, singing our song of God,

Chanting our chant of pleasant exploration.

The voices pause for a moment of reflection before both the poet and his soul are slowly and unexpectantly drawn upward with a prayer, “Bathe me O God in thee, mounting to thee.” But we have not yet reached the place of vision. That arrives as the most powerful moment of the symphony: “O Thou transcendent . . . Light of the light, shedding forth universes, thou centre of them.” These last four words are punctuated with the crash of cymbals.

O soul thou pleasest me, I thee,

Sailing these seas or on the hills, or waking in the night,

Thoughts, silent thoughts, of Time and Space and Death, like waters flowing,

Bear me indeed as through the regions infinite,

Whose air I breathe, whose ripples hear, lave me all over,

Bathe me O God in thee, mounting to thee,

I and my soul to range in range of thee.

O Thou transcendent,

Nameless, the fibre and the breath,

Light of the light, shedding forth universes, thou centre of them.

Such a vision cannot last, the poet and his soul “shrivel at the thought of God,” shrinking for a moment before regaining footing, “turning, call to thee O soul, thou actual Me,” the one who has “swellest full the vastnesses of Space.” The chorus singing, “Greater than stars or suns,” declares that God’s being transcends the whole of His creation. But in spite of infinite vastness ahead of them, and its mystery, they, “hoist instantly the anchor!”

Swiftly I shrivel at the thought of God,

At Nature and its wonders, Time and Space and Death,

But that I, turning, call to thee O soul, thou actual Me,

And lo, thou gently masterest the orbs,

Thou matest Time, smilest content at Death,

And fillest, swellest full the vastnesses of Space.

Greater than stars or suns,

Bounding O soul thou journeyest forth;

Away O soul! hoist instantly the anchor!

Cut the hawsers — haul out — shake out every sail,

After hints of a mystical vision, their searching will continue in “the deep waters only.” Here they “will risk the ship, ourselves, and all.” After all, they ask, “are they not all the seas of God?” so why not “farther, farther sail.” The poet and his soul continue on.

Reckless O soul, exploring, I with thee, and thou with me,

Sail forth — steer for the deep waters only,

For we are bound where mariner has not yet dared to go,

And we will risk the ship, ourselves and all.

O my brave soul!

O farther farther sail!

O daring joy, but safe! are they not all the seas of God?

O farther, farther, farther sail!

There will be those who predictably read The Whitman Option with exactly the suspicion that makes them live safely indoors, so to speak. They will accuse me of recommending the words and deeds of a pantheist and accused homosexual in the place of a saint. They will be missing the spirituality of Whitman’s text and how it is deepened and amplified by the beauty of Vaughn Williams music, who himself professed agnosticism in spite of editing the English Hymnal (1906) and composing a large corpus of sacred music.

Yes, these two, Whitman and Vaughn Williams, hardly stand for role models in Christian saintliness. Yet, the beauty they created has stood the test of time, in part because each of them gave expression to our infinite desire for God in a way that made that desire palpable. We are convinced not by argument but by the extraordinary experience of encountering what they, as artists, made for us. This can be an experience of ekstasis in which we are taken out of ourselves for a time. As I once put it in an essay on Jacques Maritain’s aesthetics: in a work of art, the ecstasy of the artist meets the ecstasy of his viewer.* Needless to say, such encounters can be life-changing.

The Whitman Option is offered on behalf of those whose intellectual curiosity, aesthetic hunger, political participation, artistic creativity, and social activism is part of their daily bread. This bread feeds their souls and those who are in their care. They pray “Bathe me O Lord in thee” and live their lives in expectation of joy. They’ve decided that joy is possible, even in a wicked world. Yes, these are “reckless” souls, but they know wherever they choose to journey, “are they not all the seas of God??

****

*”The Ecstasy Which Is Creation: The Shape of Maritain’s Aesthetics,” in Understanding Maritain: Philosopher and Friend, eds. Deal W. Hudson and Matthew J. Mancini, Mercer University Press, 1987.

These clips are taken from a performance of Ralph Vaughn Williams “A Sea Symphony” at the 2013 BBC Proms conducted by Sakari Oramo with the BBC Orchestra and Chorus, and soloists Roderick Williams and Sally Matthews.