To the reader: When I gave this lecture, I ended up reading only a few parts. I told illustrative stories from my life and extemporized on its basic themes. This audience of about 220 was too alive to be read to — I enjoyed myself greatly and the audience responded warmly. Lots of questions followed, even more fun! If my children were still high school age, I would send them to WCC without hesitation.

The Point of Contact: Transcendence and Immanence

Deal W. Hudson

A Lecture at Wyoming Catholic College

April 26, 2024

There is a poem by George Herbert you may know (recite from memory).

Love Bade Me Welcome

George Herbert — ‘Love III’

Love bade me welcome. Yet my soul drew back

Guilty of dust and sin.

But quick-eyed Love, observing me grow slack

From my first entrance in,

Drew nearer to me, sweetly questioning,

If I lacked any thing.

A guest I answered, worthy to be here:

Love said, You shall be he.

I the unkind, ungrateful? Ah my dear

I cannot look on thee.

Love took my hand, and smiling did reply,

Who made the eyes but I?

Truth Lord, but I have marred them: Let my shame

Go where it doth deserve.

And know you not, says Love, who bore the blame?

My dear, then I will serve.

You must sit down, says Love, and taste my meat;

So I did sit and eat. (1)

Who made the eyes but I? Who bore the blame? The poet calls upon both creation and redemption to bring a sinner to Love’s table.

The sinner wants to become his own judge and jury, to decide whether he deserves to be in the presence of God. Love says, hey, it doesn’t work that way! ‘You, shall be he.”

You are a creature, she reminds him, whose ability to sin is a result of God’s gift of human life with freedom of choice — the eyes you mar are those God gave you.

Our creatureliness, our immanent existence is a gift of the transcendent God. The philosophers call that relation of creature to creator is one of metaphysical participation.

That participation of finite with infinite being fills us with a natural desire to unite with God, it’s built into our existence, into the desire of the senses, the mind, and the heart.

The sinner misuses that desire. He indulges in self-love. This misuse is an attempt ‘like God’ as the serpent promised (Ex 3.4); and has led humankind into the state of shame — the curse of fallenness, the fruits of vices and habits of sin.

The sinner has used his eyes in a sinful way and feels shame. All of us are lead to sin by our senses. Senses become tools and by-ways of self-love. So what does God, i.e., Love, do to reach us? He doesn’t try to circumvent them with some kind of direct illumination. God places Himself before those same human senses in order to lead us home. He uses what we have employed to sin to get our attention. His is a revelatory rescue mission in history.

Incarnatus est! The God Who created us Incarnated himself so we could see Him and hear Him with our eyes and ears, to feel his touch on our brow, to follow his life on earth and witness his ascension into Heaven. He shows us the way to salvation through the senses. And part of what we see is Christ’s flesh torn apart, nailed to a Cross, and the suffering of death. But he left us with his Real Presence, as Love says, ‘you must sit down…and taste my meat.’

Creation grounds the access of our immanent existence to transcendence, but the Incarnation is the ultimate point of contact between transcendent and immanent existence. The immanent and transcendent are fused in the dual-natured Man, and from the perspective of Hypostatic union, God takes nature itself into Himself.

Both the natural desire of our creatureliness and the act of Incarnation leave us facing a choice: where to direct our natural desire, towards what end, towards what ends leading to that end, will we choose Christ?

This choice is both philosophical and theological depending on one’s faith or lack of it. Those without faith are as subject to the choice as the believer.

Natural desire is like an internal firehose that is always turned on. We feel a force that drives us toward the fulfillment of ultimate happiness.

What we seek as fulfilling becomes our good, whether for good or for ill. (The good in the ontological, not the moral, sense.) It’s a desire that fundamentally wants more than nature alone can supply. We must be made aware of desire’s final object and be lifted up to meet Him.

It’s a force within that can lead to heaven or hell — in fact, that desire explains the depths of sin a human life can fall to. It explains the ‘I will not serve’ of Milton’s Satan (2) and the frozen lake of Dante’s (2).

When I read about or encounter the worst destructive power of pride, envy, or wrath, I know it can only be explained by the perversion of an infinite desire, a will believing it can be satisfied by evil acts.

Most of all, we must acknowledge the desire cannot be extinguished, no matter how much one claims detachment. Men and woman will choose their ultimate concern, as the Protestant theologian Paul Tillich put it, even if they are not aware of doing so.(4)

God placed within us this desire to return to him but he also placed us in a world where there are other points of contact between our immanent existence and his transcendent presence. These points of contact become signposts and excitants in our journey to Him.The Herbert poem is itself one of those — made even more so by the musical setting in the ‘Five Mystical Songs’ of Ralph Vaughan Williams. (5)

So, let us read George Herbert who sings of the urgings of Divine Love.

We live in nothing less than an experienced metaphysic of existence, the push from within towards the Good, the pull from without of all that exists, that existence being given by God Himself who is the ‘I AM WHO I AM.’ (6)

God shares his existence with beings endowed with His image who are thus able to shape that existence through our doing and making. Let’s talk about those who make, specifically those who seek to find truth, goodness, and beauty in books, music, film, poetry, sculpture, painting, dance, and fiction. And let’s talk about what happens to us at those points of contact.

Let us read Aristotle who explains why people come and go through life and why merely a few friends remain constant. (7)

Let us listen to Bruckner’s motet Os Justi — the mouths of the just — where God’s abundant and ever-flowing grace becomes audible in sound. (8) (Matched by the Dona Nobis Pacem of Bach’s B Minor Mass)

Let us watch the Danish film Ordet directed by Carl Von Dreyer, the first movie to make a divine miracle seem possible. As well as his unsurpassed film about St. Joan of Arc. (9)

Let us read Hopkins who saw Kingfishers flash fire and glorified God for dappled things. (10)

Let us look, if we dare, into the eyes of Michelangelo’s Moses whose resolute stare strips us bare. (11)

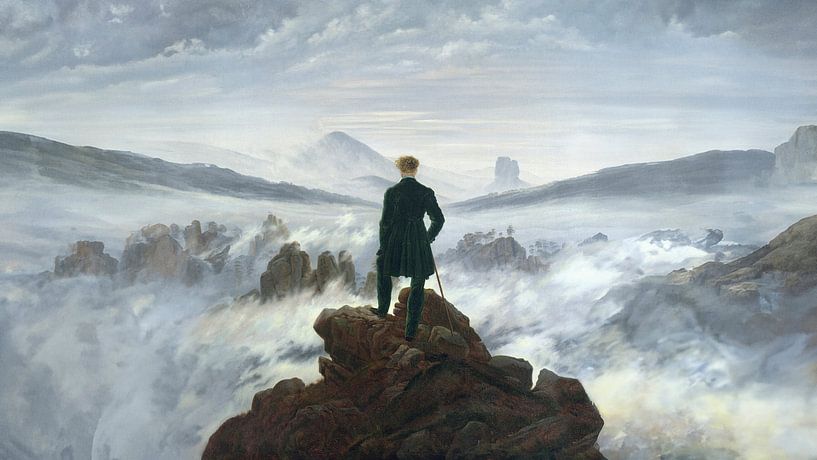

Let us gaze upon Caspar David Friedrich’s Monk by the Sea and feel ‘as if one’s eyelids have been cut away.’ (12)

Let us watch the dancing of Martha Graham who makes Copland’s Appalachian Spring into a celebration of spring, youth, and young love. (13)

Let us read Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina which exposes the tragedy of a life ruined by abandoning familial love for short-lived sensual delight. (14)

Let us enter together into the Piazza del Campo of Siena, Italy where the Blessed Mother lay down her cape creating perfect harmony. (15)

Let us ride through Monument Valley and be reminded of God the Maker Whose creation can overwhelm us with the awe of the sublime. (16)

I’ve been blessed with experiencing all these points of contact in my life, and many more — they changed me, they led me, they lifted me up. I return to them each day — I seek to live attentively as if any moment, any encounter can become a point of contact, an experience of being taken out of myself and growing towards God. (Afternoon of a Faun and Bach B Minor Mass).

I seek this contact every day, for more than therapeutic reasons, but because I crave a deeper knowledge, a clearer vision, a greater capacity for love.

As Jacques Maritain has noted, ‘Thomist have sensitive bodies,’ meaning they’re receptive to the world, not detached from it. (18) Our happiness in this life is a constant receiving, beginning with the reception of life (esse) itself, leading to a passion of graduated satisfactions, actions, and insights that form us as a person over a lifetime.

Our ecstasy is a response to the ecstasy of creation experienced by the artist, the intellectual, the performer, the craftsman. Such encounters can be life-changing. This going-out-from-ourselves inclines us towards the experience of kenosis, or self-emptying which Hans Urs von Balthasar call the ‘Christ-form.’ (17)

The desire for happiness, first imperfect, then for the perfect happiness revealed by faith doesn’t go away when you reach seventy-four, if anything, it’s more intense because the time left is shorter — you can see the end. As the writer and apologist Leon Bloy, mentor to Jacques and Raissa Maritain, once said, ‘the only true sadness . . . is not to be a saint.’ (19) Age teaches you that natural desire’s only true fulfillment is the vision of God.

But every human person needs to be made alive to the meaning of this yearning from within. This is why I began my book How to Keep from Losing Your Mind with a poem by Rainer Maria Rilke, the ‘Archaic Torso of Apollo.’

We cannot know his legendary head

with eyes like ripening fruit. And yet his torso

is still suffused with brilliance from inside,

like a lamp, in which his gaze, now turned to low,

gleams in all its power. Otherwise

the curved breast could not dazzle you so, nor could

a smile run through the placid hips and thighs

to that dark center where procreation flared.

Otherwise this stone would seem defaced

beneath the translucent cascade of the shoulders

and would not glisten like a wild beast’s fur:

would not, from all the borders of itself,

burst like a star: for here there is no place

that does not see you. You must change your life. (20)

In presence of such beauty, we feel the same impulse, that we ‘must change’ our lives. Why? Because it makes conscious, makes luminous, the inner aspiration we have for higher things, better lives, and true happiness — Rilke states it plainly, “for here there is no place/ that does not see you.” And in being seen, we cannot hide from who we really are and our aspiration for a true final end.

Jacques Maritain describes another aspect of this experience this as beauty “limps.” The beauty of a poem like Herbert or Rilke imparts insight and arouses delight but when those moments pass we search for the beauty and consequent satisfaction that is never-ending. We come face to face with our desire that outstrips the capacity of nature to fulfill it. So we are spurred on.

Charles Baudelaire, whom T.S. Eliot called the greatest Christian poet since Dante (21) wrote: “When an exquisite poem brings tears to the eyes, those tears are not proof of an excess of joy, they rather the testimony of an irritated melancholy, a demand of the nerves, of a nature exiled in the imperfect and desiring to take possession immediately, even on this earth, of a revealed paradise.” (22)

Hans Urs von Balthasar sets the bar even higher when in Glory of the Lord — he warns those who “sneer” at beauty “as if she were the ornament of a bourgeoise past” of becoming unable to pray or even love.’ (23) Beauty pulls us out of and beyond ourselves. It can eviscerate the refusal in all of us — how can we resist the bird who sings in the tree above are heads? Some do, and they are dying inside, insisting their misery is somehow heroic.

Obviously, I am not one of those whom Von Balthasar describes as sneering at beauty. But ugliness is another matter. I’ll confess to finding it harder to pray when guitars, bongo drums accompany so-called Praise and Worship music is being sung — usually half-heartedly — in Holy Mass. Why Bad Taste, the Banal, and the actively Ugly, were allowed to take over Catholic liturgy is story of its own, which I and others, notably Thomas Day in Why Catholics Don’t Sing (24), have told before. Much of the Catholic worship I have experienced represents a surrender to what is best described as Kitsch.

Kitsch supplies an easy, feel-good experience in place of what genuine, sacred art provides – a challenge, eliciting a deeper understanding, a sense of awe at the mystery of what can’t be known in this lifetime. Catholic kitsch presents its figures as easily digested, non-threatening, and makes no demand on the mind or the imagination. Kitsch glorifies the superficial and treats sentimentality as holy awe.

The Czech writer Milan Kundera calls kitsch self-congratulation and describes it as the “second tear”: “Kitsch causes two tears to flow in quick succession. The first tear says: How nice to see the children running in the grass! The second tear says: How nice to be moved, together with all mankind, by children running in the grass! It is the second tear which makes kitsch, kitsch.” (25)

The German writer and Catholic convert, Herman Broch, considered kitsch as a form of deception. When kitsch supplies instant comfort, it denies the complexity of what is being represented: Broch calls it a “counterfeit image” allowing someone to see only what they want to see. Kitsch obscures reality. (26)

How the Lord’s presence in the Mass can be celebrated in such a way is my biggest disappointment in my forty years as a Catholic. But the let down has been more than compensated for by spiritual riches of Catholic Christianity including the privilege of being at a place like this, meeting people like you, learning from and sharing with you.

Let us sing together the single melodic line of the chant and organum we inherited from the early middle ages and the finely wrought polyphony of Dufay, Palestrina, and Victoria.

There is the fulfillment of a point of contact, but there is even greater satisfaction in sharing it, and seeing in another’s eyes what you beheld. This is the great privilege of the teacher: to witness that moment of discovery when the greatness of a great book suddenly illumines their student’s face.

The critic and essayist George Steiner put it so well when he said teachers are “the postmen of the Absolute.” (27)

I recall vividly the times students, friends, and family members gave my recommendations a chance and got hooked, not to please me but they were enveloped by the power of an idea, an object, a place. (Even lately golfers….)

In my lifetime, I’ve witnessed again and again the intrinsic power of greatness in things on the inner life, on the soul.

Let us read of Plato’s Socrates whose sacrifice prefigured the Man who died when he had the power at hand to save himself. (28)

Let us read St. Thomas who defended the goodness of Satan against those who denied the goodness of all His creation. (29)

Let’s watch Waiting for Godot where Becket exposes the self-imposed despair of modern man. (30)

Let us read St. Paul who tells us to finish the hard race of loving God and one another without ever keeping a list of wrongs. (31)

Let us read Baudelaire who writes ‘To the Reader’ in Les Fleurs de Mal reminding us not to look down upon the world of boredom and sensuality he depicts. We are among them. (32)

Let us read Walt Whitman who yearns to feel the total presence of God, ‘Bathe me O God in thee, mounting to thee,

I and my soul to range in range of thee.’ (33)

Let us listen to Mahler’s 8th symphony where our eyes are drawn upward as if in a Gothic cathedral by the singing of Goethe’s words ‘Blicket Auf’ (Look Up) as Faust approaches his salvation. (34)

Let us watch Robert Bresson’s film ‘Au Hasard Balthasar’ whose main character, a donkey, walks the via dolorosa of Christ until he meets a child who loves him. (35)

Let us read Maritain who warned 80 years ago of the day approaching when we lose the ability to rationally defend the principles at the basis of our civilization. That day, sadly, is here. (36)

Let us read Etienne Gilson who found in St. Thomas the solution to self-love — let it be God’s love with which we love ourselves. (37)

Let us read Flannery O’Connor who reveals the desire of God manifested through all the seven deadly sins, and the grotesques we would prefer to ignore but hold a mirror to our faces. (38)

The beauty these men and women created has stood the test of time, in part because each of them gave expression to our desire for God in a way that made that desire palpable, it’s fulfillment possible.

We are convicted not by argument but by the extraordinary experience of encountering what they, as artists, made for us.

You may ask me if all the above is mere aestheticism? I think there was time in my life when it was, then I met Soren Kierkegaard who blasted me out of the aesthetic into the ethical and beyond. Kierkegaard portrayed the dead ends of the aesthete which I had already floundered against. (39) It took St. Thomas, Maritain, Gilson, and Von Balthasar to take me the rest of the way to meeting Christ Himself in the Eucharist. But they did it in a way that did not ask me to confine myself to Scripture alone, to avoid the arts of the beautiful or the thoughts of the philosophers. They welcomed me into an entire Catholic culture.

As I Catholic, I found the religious life embraced the aesthetic experience in all its dimensions but warned as Flannery O’Connor did in seeking “instant uplift,” the feel-good Christianity of back-patting kitsch. (40) Christians hold onto their kitsch like they fail to put away ‘childish things,’ mistaking familiarity for profundity. Kitsch feels to them like safe ground, standing at a distance from the danger which is ‘Hollywood,’ or from the threat of ideas they don’t recognize, or from the voices who tell them to study history lest they repeat it. (Don’t let your focus on the Great Books discourage your need for a deep dive into the historic essentials of the past.)

But if you were to ask me what has the greatest beauty of them all, I would have to say ‘sacrificial love.”

This love is portrayed powerfully in The Heart of the World by Hans Urs von Balthasar:

“For his [Christ’s] weakness would already be the victory of his love for the Father, reconciliation in the eyes of the Father, and, as a deed of his supreme strength, this weakness would be so great that it would far surpass and sustain in itself the world’s pitiful feebleness. He alone would henceforth be the measure and thus also the meaning of all impotence. He wanted to sink so low that in the future all falling would be a falling into him.…” (41)

“All falling would be a falling into Him….” I never really knew what grace meant until I read that passage. “I, the unkind, ungrateful” could be held in the arms of God.

Suddenly the deeper meaning of all those crucifixes I had stood before became intensely personal to me — no matter how far I fall, no matter how filled with shame I may become, I fall into the arms of Jesus Christ. Why? Because He “bore the blame” for me, and all of us.

Knowing this, believing this, changes a person. It changes how and where they see beauty, where we meet the points of contact.

Years ago, as a graduate student at Emory University, I had a professor of Romance Languages named Arthur Evans. He had caught Parkinson’s but while we were able we still went to lunch regularly. We took lunch one day in a less desirable part of Atlanta. As we left I saw a beggar squatting beside the sidewalk which I passed by.

When I turned to speak to Dr. Evans he wasn’t there. I looked back: he was holding the beggar’s hands putting money into them and looking closely into his eyes — he had brilliantly blue eyes — and spoke words of encouragement to him.

I was simultaneously ashamed but even more I was transported by the beauty of this moment. The Parkinson’s shook his hands but he held tightly to the man in need. The man I had ignored. Well, never again. The beauty of that moment became one standard for my moral and spiritual life.

That moment contained what I referred to before as Von Balthasar’s Christ-form, the self-emptying love that has saved the world through the work of Jesus Christ. Look closely at some of the works of art that possess greatest power over you, and its very likely the Christ-form is present.

In my case, I will mention three more examples: the film, A Man for All Seasons (42), the novel by Sigrid Undset, Kristin Lavransdatter (43), and the great Beethoven String Quartet #14, Op. 131 (44). First, a man of power gives up his power and life in martyrdom; second, a woman of self-destructive egotism and impulsiveness lets go of both by surrendering to God and taking the veil; third, the creator of Romantic rebellion in modern music trades his heroic resistance for spiritual resignation and comfort.

Then there’s the famous assertion from Prince Mishkin in Dostoevsky’s The Idiot that ‘beauty will save the world.’ (45)

In response, we can say with confidence that it will not be beauty alone but beauty allied with all the ways the actuality of human existence is pulled, prodded, even crushed, towards its perfection.

The beauty of all all forms of art, like natural beauty, are a gift. But with that gift comes both a challenge and responsibility.

We must be the fool who differs from almost everyone else in how we speak, what we speak about, what we value, and what we love.

We must sound like the idiot who speaks of Shakespeare, when others speak only of sports, illnesses, and grandchildren.

We must be the oddball who prefer the waltz over the butt-bump and pelvic grind to monotonous and meaningless noise.

We must be teachers, by word and by witness. Postmen of the Absolute.

To do that, you must have the courage and insight to follow where Beauty leads, and that is, up and beyond, towards what is greater for ourselves and others.

The greatness of great books is no static claim;

it asserts and promises a dynamic encounter,

one that leaves us changed,

wiser but longing for more wisdom;

satisfied but glimpsing a perfect satisfaction,

challenged but grateful to be learning —

in all a wounded happiness,

but a happiness that leads to the one that is final.

Thank you.

A List of Examples Mentioned:

1. George Herbert, “Love III,” “Love bade me welcome,” The Temple: Sacred Poems, 1633.

2. John Milton, Paradise Lost, Book 1, 105ff.

3. Dante Alighieri, Inferno, Canto 34.

4. Paul Tillich, The Dynamics of Faith, 1957, Chapter 1.

5. Ralph Vaughan Williams, “Love Bade Me Welcome,’ Five Mystical Songs, 1911. Listen to the recording sung by baritone, John Shirley Quirk.

6. Exodus, “I AM WHO I AM,” Exodus 3,14.

7. Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, Book 8

8. Anton Bruckner, “Os Just,” Five Motets; Listen to the recording conducted by John Eliot Gardiner.

9. Carl Theodor Dreyer, Ordet, 1955 (Danish). Available to stream at Criterion Collections; also available on DVD.

10. Gerard Manley Hopkins, “As Kingfishers Catch Fire,” 1877.

11. Michelangelo, Moses, 1515, Basilica of St. Peter in Vincolo, Rome.

12. Caspar David Friedrich, “Monk by the Sea,” 1810, Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin. Heinrich von Kleist, poet, dramatist, novelist ( 1777 -1811 ) wrote of “Monk by the Sea,” it feels “as if one’s eyelids have been cut away.’

13. Martha Graham, Appalachian Spring, a 1944 ballet composed by Aaron Copland and choreographed by Martha Graham. An early performance can be found on YouTube.

14. Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina, 1878. I wrote at length on this issue: https://philpapers.org/rec/HUDCAK-3. It’s also addressed in a chapter of my book, Happiness and the Limits of Satisfaction, 1995. https://philpapers.org/rec/HUDCAK-3

15. Piazza del Campo, Siena, Italy, 1349. The sections were designed to resemble the folds in the Virgin Mary’s cloak.

16. Monument Valley, Arizona, used often in John Ford western films. Its Sand buttes rise as high as 1000 feet.

17. Hans Urs Von Balthasar, The Glory of the Lord: A Theological Aesthetics, vol. 1, Seeing the Form 2009, 216—218.

18. Jacques Maritain, A Preface to Metaphysics: Seven Lectures on Being, 1948, 23.

19. Leon Bloy, The Woman Who Was Poor, 1897, 1939 English translation: “The only real sadness, the only real failure, the only great tragedy in life, is not to become a saint.”

20. Rainer Maria Rilke, Archaic Torso of Apollo, New Poems, 1908 (German).

21. Jacques Maritain, Creative Intuition In Art and Poetry, 1953, 167. Maritain is quoting the French artist Jean Cocteau.

22. Charles Baudelaire, Selected Writings on Art and Literature, Edited by P.J. Charvet, 1995.

23. Hans Urs Von Balthasar, The Glory of the Lord: A Theological Aesthetics, vol. 1, Seeing the Form, 2009, 18.

24. Rev. Thomas Day, Why Catholics Can’t Sing, revised edition, 2013.

25. Milan Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, 1984.

26. Herman Broch, Geist and Zeitgeist: The Spirit in an Unspiritual Age, 2003.

27. George Steiner, I cannot find this citation, but I wrote of it elsewhere, “‘The Absolute,’ as Steiner called it, is not delivered through short term memorization. When the Absolute arrives it changes the student, it sets loose a desire, a love, an appreciation that acts like a ‘gateway drug,’ leading to more and more powerful and substantial experiences of learning.”

https://www.catholic.org/news/national/story.php?id=54332

28. Plato, Apology and Crito.

29. St. Thomas, Summa Theologiae, Part 1.5.3.ad 2; Part 1.6.3. ad 3. When I first read these passages, I was accompanied by a redbird. https://thechristianreview.com/the-day-a-red-bird-sang-st-thomas-aquinas/

30. Samuel Becket, Waiting for Godot, 1953.

31. St. Paul, 2 Timothy 4,7.; I Corinthians 13.

32. Charles Baudelaire, “Au Lecteur” (To the Reader), Les Fleurs du Mal (The Flowers of Evil), 1857. T.S. Eliot, Selected Essays, 1930, ‘Baudelaire’; also, Eliot writes, “Baudelaire perceived that what really matters in Sin and Redemption . . . and the possibility of damnation is so immense a relief in a world of electoral reform, plebiscites, sex reform and dress reform, that damnation itself is an immediate form of salvation — of salvation from the ennui of modern life, because it at last gives some significance to living.”

33. Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass, Book 28, 8.

“Bathe me O God in thee, mounting to thee, / I and my soul to range in range of thee. / O Thou transcendent, / Nameless, the fibre and the breath, / Light of the light, / shedding forth universes, thou centre of them, / Thou mightier centre of the true, the good, the loving, / Thou moral, spiritual fountain—affection’s source—thou reservoir….” Try to hear the setting of these words by Ralph Vaughan Williams in his 1st Symphony called the “Sea Symphony.” I recommend the recording conducted by Bernard Haitink.

34. Gustav Mahler, 8th Symphony, 1906. A two-part setting of Veni creator spiritus and Goethe’s Faust for chorus, soloists, and orchestra. Listen to the version conducted by George Solti. There are few more moving moments in music when the “blicket auf” is sung properly by the tenor soloist.

35. Robert Bresson, Au Hasard Balthasar, 1966 (French), inspired by a scene from Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Idiot 1869.

36. Jacques Maritain, I cannot find this citation which I first read fifty years ago.

37. Etienne Gilson, The Christian Philosophy of the Middle Ages, 1956, Chapter 3.4.II.

38. Flannery O’Connor, Mystery and Manners, 1957, 36-50.

39. Soren Kierkegaard, Either/Or, two volumes, 1843, contrasts the aesthetic and ethical ways of life.

40. Flannery O’Connor, Mystery and Manners, 1957, 165. “Today’s reader, if he believes in grace at all, sees it as something that can be separated from nature and served up to him raw as Instant Uplift.”

41. Hans Urs Von Balthasar, The Heart of the World, 1980, 110.

42. A Man for all Seasons, directed by Fred Zinnemann, screenplay by Robert Bolt, starring Paul Scofield, 1966.

43. Sigrid Undset, Kristin Lavransdatter, 1922, 3 volumes (Norwegian translated twice into English; start with the translation by Tiina Nunnally).

44. Ludwig von Beethoven, Opus 131, String Quartet #14 in C♯ minor (1826). There are many good recordings, but I am partial to the Emerson Quartet.

45. Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Idiot, 1869.

Deal W. Hudson

hudsondeal@gmail.com