Martin Luther did not set out to cause a reformation, as it became, but to rid the Catholic Church of the corruption that was taking place. After petitioning his bishops and the Pope for corrective measures and receiving no substantive response, he went public. His subsequent edicts had vast religious political ramifications that quickly extended to the fledging English colonies in the New World.

Luther’s love of the Catholic Church was tried by the corruption of her clergy, the bulwark of Her apostles. His exposure of the Church’s ills coincided with rise of nationalism in Europe, leading to gradual political, as well as religious, separation from the rule of the Roman Pontiff.

The most visible separation was that of Henry VIII, with his declaration that he was head of the church, not the Pope. Though Henry VIII had been a foe of Luther and Lutheranism, his breaking with Rome and revoking of papal authority had the effect of transporting Luther’s anti-Catholicism into the foundation of its American colonies.

The first arrivals, by planting the Anglican Cross, brought the English penal codes which determined the course for religion, politics, and laws for all inhabitants. These codes made it treason for any Englishman ordained a Catholic priest abroad after 1559 to come into or remain in England and a felony for anyone to shelter or assist such a priest.

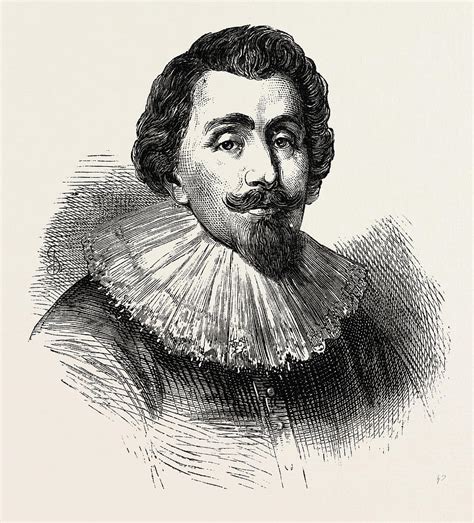

An anti-Catholic furor broke out, however, with the charter granted by Charles I to Lord Baltimore — George Calvert — for the colony of Maryland in 1632. This contained the most comprehensive grant of civil and political authority and jurisdiction that ever emanated from the English Crown: sole proprietorship of the colony.

Calvert’s vision was to create a safe haven for Catholics with the unprecedented policy of coexistence of other religions. The immediate uproar in the adjacent Virginia gave vent in the resentment and vengeance of William Claiborne, a member of the government council, who obtained a license from Governor Harvey to establish a trading post on Kent Island, the largest island in the Chesapeake Bay, as convenience to himself and an irritant to the Catholics.

He never acquired nor requested to own any part of the land, but simply became a squatter. He vigorously refused to acknowledge Lord Baltimore’s charter and his authority and incited the local tribes against the Popish invasion. In all this, Claiborne had the backing of the Council of Virginia, the unrelenting enemy of the Catholic colonists.

His specific aim was to abolish and annihilate any semblance of papacy in the English New World. Virginia as a royal colony had no authority to dictate to Maryland, but they still viewed their statues of religious laws as superseding those of Lord Baltimore, claiming treason against the established Church of England and the colony.

“Whereas it was enacted that no popish recusants should at any time hereafter exercize the place or places of secret councellors, register or comiss: surveyors or sheriffe, or any other publique place, but be vtterly disabled for the same. . . .”

Not only were Catholics not allowed to hold these offices in the Commonwealth of Virginia, but also any Catholic priest was allowed only five days in the Commonwealth before being arrested:

“And that it should not be lawfull under the penaltie aforesaid for any popish priest that shall hereafter arrive to remaine above five days after warning given for his departure by the Governour or comander of the place where he or they shall bee, if wind and weather hinder not his departure.”

Anti-Catholic laws such as this were on the books in every colony and were not abolished until well into the 18th century. It could be argued, given current events, that this visibly embraced anti-Catholic fervor has merely gone underground in our United States and remains a powerful force in our culture and politics.