If you give only one book for Christmas, I recommend The Complete Works of Primo Levi (boxed in 3 volumes). The books are beautifully bound and edited, the pages sturdy, the fonts well-chosen, and the lay-out assures no hot lights or squinting are required for reading. The entire collection has been newly translated.

Levi’s Auschwitz memoir, If This Is a Man (1947), should be required reading for every high school senior — his account focuses on the prisoners themselves, how they struggled to adapt to their captivity, their hunger, their slave labor, their constant beatings, and fear of death. Levi speaks as a scientist turned humanist and philosopher, as an ethnic Jew who looks upon religion appreciatively but from the outside. One might say this book contains a portrait of ‘humanity in the raw’ but the tone of condemnation is reserved only for the most egregious acts of inhumanity. As he wrote years later in the deposition used at the trial of Adolf Eichmann:

“‘Forgive’ is not my word. It is inflicted on me, because all the letters I receive, especially from young, Catholic readers, have this theme. They ask if I have forgiven. I believe that I am in my way a just man. I can forgive one man and not another; I’m able to pass judgment only case by case. If I had had Eichmann before me, I would have condemned him to death. Indiscriminate forgiveness, as some have asked me for, is not acceptable to me.”

Most readers will turn first to Levi’s major works found in these volumes, including The Truce (1963) where he describes his long return home to Turin, Italy from Auschwitz, including some months in a Soviet facility for concentration camp survivors. His circuitous train journey took him through most of Eastern Europe where he witnessed the spectacle of displaced persons picking there way through the carnage, trying to find their homes.

His final reflection on Auschwitz was published in 1986, The Drowned and the Saved, where he asks aloud why some survived, including himself, while most perished. At a moment when he knows he faces being selected to die, Levi is tempted to pray to the God he believes does not exist, but resists, explaining, “equanimity prevailed.”

In The Periodic Table (1975), the scientifically trained Levi uses each of the elements to write a short chapter on his experiences, beginning with his doctoral studies in chemistry under the Italian Fascists, his arrest and interrogation as an anti-Fascist partisan, his transport to Auschwitz, and life after his return to Italy.

In addition to these books, the Complete Works contains six volumes of short stories, three essay collections, two novels, two poetry volumes, and a collection of interviews. A critic I much admire, Michael Dirda, admits Primo Levi has been “somewhat neglected,” writing in the Washington Post, “Whether as witness or imaginative artist, Levi stands high among the truly essential European writers of the past century.”

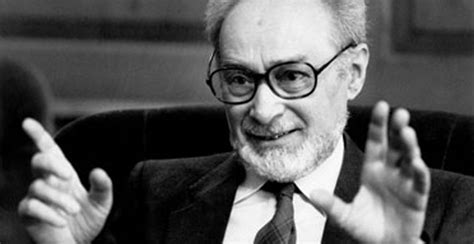

However, the novelist Philip Roth, summarizes Levi’s achievement most succinctly: “With the moral stamina and intellectual pose of a twentieth-century titan, this slightly built, dutiful, unassuming chemist set out systematically to remember the German hell on earth, steadfastly to think it through, and then to render it comprehensible in lucid, unpretentious prose.”

Primo Levi committed suicide in 1987, jumping from an interior landing of his apartment building and falling to his death on the ground floor. It was well-known among his friends that he suffered badly from depression. A few friends believe he lost his balance, arguing as a chemist Levi would have devised an easier way to die. A fellow Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel understood it best, perhaps, when he said, “Primo Levi died at Auschwitz forty years later.”

This publication of Levi’s complete works, along with the subsequent spike of recognition, comes at a good time in Western culture. We have been witnessing another form of incomprehensible inhumanity, beginning with the Al-Qaeda attack of 9/11, continuing with the barbarisms of the Islamic State (ISIS). We are a civilization under attack and a people struggling with our hate of an enemy who targets the innocent.

The witness of Primo Levi, found in these three volumes, will not remove our hate — Levi would not have approved of that — but reminds us what can happen among those who are threatened, which means the entirety of Western peoples. The determination to defeat the enemy will not be uniform: there will be those who put their comfort and survival ahead of any other concerns, even the defense of civilization itself. As a result, they will turn their fury towards those who place themselves in the front lines.