The film “Christopher Columbus” by David MacDonald in 1949 is the old standard version of the story honoring the ingenious hero who discovered the western hemisphere. Hal Erickson, however, called it “Reverent to the point of tedium…” Afterward, the reputation of the explorer became increasingly questioned, criticized and even attacked. Now, films about Columbus are increasingly irreverent to the point of fury.

The six-hour epic miniseries in 1985 with Gabriel Byrne was still relatively fair, but highlighted the excesses of colonization. Erickson says that it adds a “Harlequin Romance” to the story. Then, for the 500th anniversary in 1992, there were two. Christopher Columbus: The Discovery with Georges Corraface dealt more with the process to get across the sea than the effect, yet the famed cast was poorly selected. Then, 1492: Conquest of Paradise with Gérard Depardieu was practically a horror movie.

We now live in a time of historical revisionism, which smears the glories of the Christian past while dignifying pagan cannibals as the victims of exploitation. Although mistreatment by conquistadors is undeniable, that hardly casts a shadow on the wonderful Christianization of the New World. The actual history is more religious than economic.

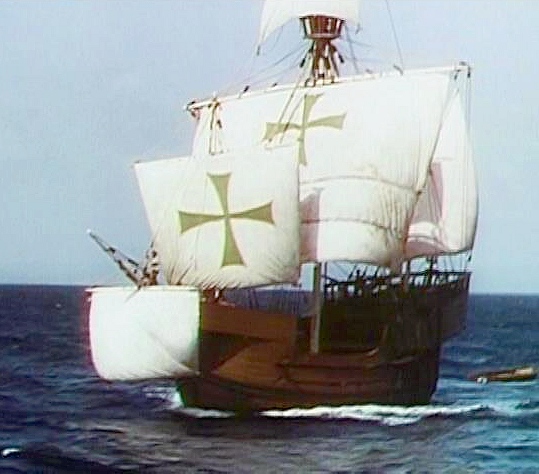

Providentially, the name “Christopher” means “Christ-bearer” and “Columbus” signifies “dove,” a symbol of the Holy Spirit. The flagship was the Santa Maria, the sails were emblazoned with the Cross and they deliberately brought Christianity to unbelievers. Bishops and priests were involved, and more or less included in casts, with more or less favorable scripts.

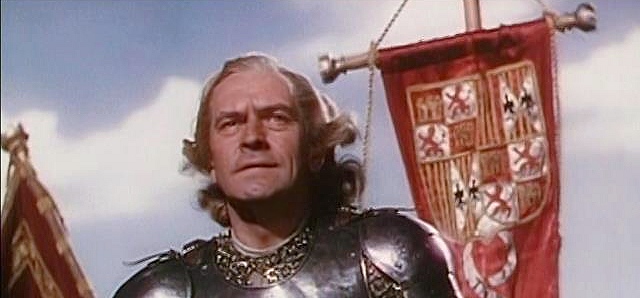

In this film, the splendid Felix Aylmer plays Father Perez. Columbus, played with flair by Fredric March, actually visited the Franciscan Friary of La Rábida in 1490. Although he tries to take advantage of the priest to gain access to the Queen, he is a man of faith. Columbus was actually a member of the Franciscan Third Order, a lay tertiary. Before they embark, Franciscans sing the Salve Regina (Hail Holy Queen).

Finally, Father Perez prevails upon her majesty. Coincidentally, here at Saint Dominic’s Church in Washington, we have a stained-glass window depicting the Dominican professor, Diego de Deza, sponsoring the explorer before Queen Isabella, assuring her that the world is round. That was not a “crackpot” idea because Saints Albert and Thomas had taught that centuries earlier.

Martin Alonso Pinzon, the captain of the Pinta, however, disobeys the admiral and leaves. Meanwhile, Columbus continues to explore and discover places, like Cuba, and things, like hammocks and tobacco. On Christmas Day, the Santa Maria ran aground, so Columbus decides to leave 40 men ashore to establish a settlement with his friend, Diego, as governor. Columbus returns on the Niña. He is met with cheers and flowers by the people. He comes before the king and queen with pomp and fanfare. At the banquet, Columbus shames his rival, Bobadilla, by teaching that anything is easy when someone shows you how.

Did he deserve more or was he the victim of his own poor judgment and pride? The film handles these delicate matters with balance. He knew that his fame would be undying, but never foresaw how his reputation would be spoiled by the modern movement against Christian civilization. The audience is rightly motivated to feel pity for the man. In our times, with egalitarian globalistic secularism, it is refreshing to remember the inestimable good that Christopher Columbus accomplished. Although some critics may rate this the worst film about the subject, I say that films about the discoverer of America only got increasingly worse afterward. Hence, this is the best.